What We Know and Don’t Know about the Cyberattacks Against Ukraine - (updated)

Dozens of government agencies in Ukraine were targeted in a web site defacement campaign; around the same time some of the same agencies were infected with a destructive wiper. What happened?

Last week dozens of government agencies in Ukraine were targeted in a web site defacement campaign in which hackers replaced their main web page with a politically charged message. Although the message asserted that the hackers had also stolen data from the agencies, the government was quick to announce that data had not been stolen.

Over the weekend, however, Microsoft announced that it detected destructive wiper malware on the systems of several government entities in Ukraine — including some whose web sites were defaced. Wipers generally delete or overwrite important system files, rendering systems unable to boot up or otherwise operate. But it's not clear if the wiper was actually launched on any systems or just installed on them in preparation for a future wipe.

To help understand the incidents that are still unfolding, I’ve compiled what is currently known and unknown.

What Happened?

Shortly after midnight last Thursday, and following three-days of failed negotiations between the US, Russia and NATO over Russia’s troop buildup on Ukraine’s border, hackers defaced or in some cases attempted to deface about 70 Ukrainian web sites, many of them top government agencies. They replaced the main web page of about a dozen sites with a threatening message to “be afraid and expect worse.”

The affected sites include the ministries of foreign affairs, defense, energy, and education and science, as well as the State Emergency Service and the Ministry of Digital Transformation, whose e-governance portal gives the public digital access to dozens of government services.

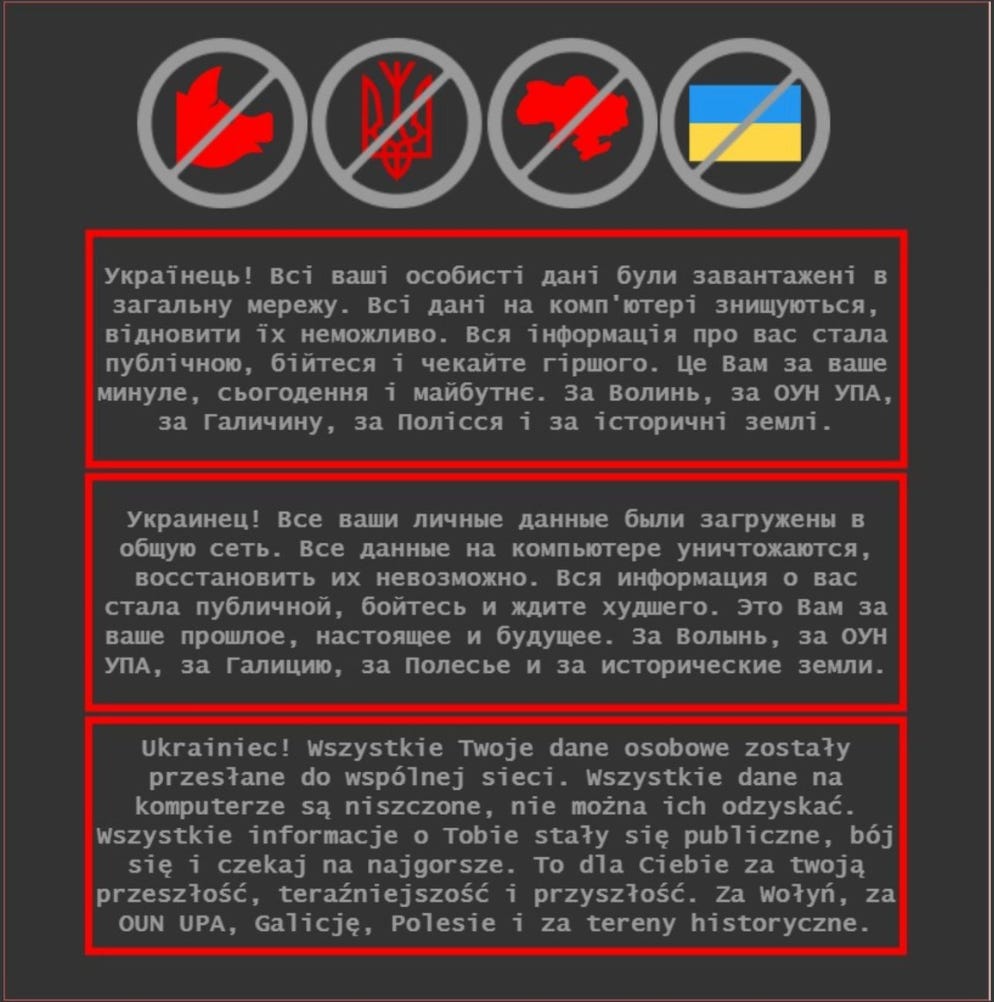

The defacement message posted to the Ministry of Foreign Affairs web site was written in Ukrainian, Russian and Polish and read: "Ukrainian! All your personal data was uploaded to the public network All data on the computer is destroyed, it is impossible to restore it. All information about you has become public, be afraid and expect the worst. This is for your past, present and future. For Volyn, for the OUN UPA, for Galicia, for Polissya and for historical lands.”

A ministry official tweeted that Ukraine had been hit with a “massive cyberattack.” But although many sites can be defaced en masse, on their own such campaigns are not significant or considered massive.

“Though an incident hitting several targets simultaneously may at first appear to be a complex, advanced operation, they could be the result of access to a single content management system [that maintains multiple web sites],” John Hultquist, vice president of intelligence analysis at Mandiant said in a statement at the time. “It’s important not to overestimate the capability necessary to carry out this attack.”

The sites quickly disappeared, as administrators took them offline to remove defaced pages and investigate the incidents. By the end of the weekend nearly all sites had been restored.

Although the defacement message on the Ministry of Foreign Affairs web site indicated that data had been siphoned and would soon be leaked, there was no evidence that data was taken, and in any case, if the theft was limited to the sites that were defaced, web servers for web sites generally do not have important data to steal.

The warning that “all data on the computer is destroyed,” also did not bear fruit. Victor Zhora, deputy director of Ukraine's State Services for Special Communication and Information Protection, said that in one case the portal for an agency that registers insured vehicles had some data deleted from its front-facing portal, but back-end databases were intact. The agency took down its web site and is restoring the portal from backup data.

The defacements were performed manually — not through a script set up to deface automatically at an appointed time. This indicates multiple actors coordinated the defacements, says Zhora. The deletion of data from the vehicle insurance portal also was done manually.

It also appears that the defacement may have been an attempt at a false-flag operation to blame Poland. The defacement message posted to the Ministry of Foreign Affairs web site appears designed to stir up division between Ukraine and Poland by making it look like it was written by Polish patriots. And metadata for the image used in the defacement suggests it originated from Poland. But Polish journalists were quick to notice that the Polish text in the defacement had stylistic problems that indicate a non-Polish speaker wrote it and that the text was probably produced through Google Translate.

On Friday, DDoS campaigns also hit a number of the affected government agencies — these campaigns involve a flood of traffic sent to web servers to deliberately prevent legitimate traffic from accessing sites. And on Monday, another defacement occurred, this one against a web site for Pro Zorro for government procurements.

How Did the Hackers Pull Off a Mass-Defacement?

Investigators believe they may have used multiple methods.

Most of the affected web sites were using the same content-management program — OctoberCMS — which led investigators to believe the hackers had compromised the web sites using a known vulnerability in the OctoberCMS software. But about 50 of the 70 affected sites were also developed and managed by a Ukrainian company called Kitsoft. Investigators eventually determined that Kitsoft had been compromised, which allowed the hackers to gain access to Kitsoft’s administrator panel and use the company’s credentials to deface customer web sites.

Not all of the affected sites are managed by Kitsoft, however, so investigators still believe some of them may have been compromised either through a vulnerability in the OctoberCMS system or through some other shared software. They are also considering whether the attacks used the Log4j vulnerability recently discovered in an open-source library that is used by numerous software programs.

What Happened Next?

Two days after the defacements occurred, Serhiy Demedyuk, deputy secretary of Ukraine’s national security and defense council, told Reuters that the defacements were "just a cover for more destructive actions that were taking place behind the scenes and the consequences of which we will feel in the near future.”

He didn’t elaborate, but hours later Microsoft announced that on the same day the defacements occurred, Microsoft detected destructive malware on systems belonging to “several Ukrainian government agencies and organizations that work closely with the Ukrainian government.”

Microsoft didn’t identify the agencies by name, but said they included ones that “provide critical executive branch or emergency response functions” as well as an IT firm that manages websites for public and private sector clients, including government agencies whose websites were recently defaced.” Microsoft didn’t name the IT firm, but the description fits Kitsoft. Kitsoft appeared to confirm in a message posted to its Facebook page on Monday that it was infected by the wiper and indicated that some of its infrastructure was damaged. But company spokeswoman Alevtina Lisniak seemed to walk back from this in an email.

“Several parts were infected by viruses and therefore compromised, so we decided to reinstall these parts from scratch,” she wrote. Asked to clarify if Kitsoft was or wasn’t infected with the destructive wiper, she said it was still under investigation.

Kitsoft provided further clarification on Tuesday, after it’s original response to Zero Day. The company’s spokeswoman now says that the “viruses” she was referring to obliquely were components of the WhisperGate wiper and that the wiper had overwritten the master boot records — the portion of the hard drive that is responsible for launching the operating system on a machine when it is booted up.

“We discovered some overwritten [master boot records] and then stopped the infrastructure to prevent further attack development,” Lisniak writes. This suggests that only the wiper’s first stage may have been activated, but this is still unclear. See below for how the wiper works.

The malware, which Microsoft is calling WhisperGate, impersonates ransomware on its surface. But this is a cover for its underlying, more destructive capability. WhisperGate is designed to wipe or overwrite critical files on infected systems to render the systems inoperable.

How Does the WhisperGate Wiper Work?

WhisperGate has three stages. Microsoft’s description is a bit unclear, but it appears that this is how it works. In the first stage, the hackers load WhisperGate onto a system and execute it by causing the machine to power down. The malware overwrites the portion of the hard drive responsible for launching the operating system when the machine is booted up. It overwrites it with a ransom note demanding Bitcoin worth $10,000.

“Your hard drive has been corrupted,” the note reads. “In case you want to recover all hard drives of your organization, You should pay us $10k via bitcoin wallet. We will contact you to give further instructions."

In the meantime, the second and third stages have already occurred — the malware has reached out to a Discord channel and pulled down another malicious component, which then corrupts numerous other files on the infected system.

Juan Andrés Guerrero-Saade, principal threat researcher at SentinelOne, says this is likely when the power-down occurs. When the system is turned back on, the ransom message appears. The user sees the ransomware message and believes they just need to pay money to get the system decrypted — when in fact their system has already been rendered inoperable and unrecoverable.

Guerrero-Saade says there is still so much that’s unknown about how the infections played out.

“We don't know the infection vector…we don't know how they were orchestrating the attacks,” he says. “We are very much in the early days of this analysis and suffering from a lack of visibility.”

Microsoft is unclear in its blog post whether any systems were actually wiped or if the malware was simply found on systems before the hackers initialized it with a power-down. Zhora said he was aware of some government systems displaying a ransom message and crashing, but investigators have so far been unable to confirm if the wiper Microsoft discovered was on them because the systems are not accessible. It could be that the ransomware in these cases were standard ransomware operations, he said.

Microsoft said the Bitcoin wallet address for paying the ransom received a small transfer of currency on January 14. But there was no website or support portal for victims to communicate with the perpetrators, and the ransomware note did not include a custom ID that victims are generally instructed to include in their communication with the ransomware operators so the operators can match victims to the decryption key needed to unlock their systems. All of this supports Microsoft’s conclusion that the ransom portion of the malware is just a ruse.

Are the Defacements and Wiper Related?

The fact that the wiper infected some of the same agencies that were targeted for defacement, and that it was found the same day the defacements occurred, would seem to suggest the two events are related.

But Ukrainian investigators are sifting through terabytes of logs and still don’t know if the two events are connected and whether the defacements were a cover for depositing the destructive wiper on systems, or if the timing was coincidental. They also don’t know how the malware got onto systems.

It’s also unclear if the wiper infected the same systems that were defaced. The defacements occurred on front-end internet-facing systems, not internal agency systems.

“These systems would have been pretty superficial to the actual [agency] networks,” says Hultquist.

In the Sony hack in 2014, by contrast, a defaced message appeared on worker desktop machines, and the attackers were inside the company’s corporate network and able to steal email and documents.

If the defacements and wiper were meant to be coordinated and simultaneous — a possibility since Microsoft says some of the same agencies defaced were also infected with the wiper — the timing was odd. Conducting an attention-getting defacement of web sites on the same day a wiper is installed but not launched would only draw scrutiny to the networks of those agencies, raising the potential for the wiper to be discovered before it had a chance to wipe anything.

A security researcher who goes by the name The Grugq wrote in a post that he believes the two events may have been a coordinated effort by two groups, in which the coordination failed.

“They said [in the defacement] ’your information is leaked and destroyed,’ but the news of [the wiper] wasn’t public for two days,” he told Zero Day. “That made the defacement appear like an isolated attack by some blustering idiots who couldn’t do anything.”

They should have wiped machines first, and then defaced the web sites of those same agencies, he notes. “That way the news of the [wiper attack] would be out, and then a message from the attackers should show up.”

If the coordination was done properly, they “would have been more than the sum of their parts,” he writes in his post. Instead, the delay between the incidents “meant that each was interpreted independently.”

Who Is Responsible for the Defacements and the Wiper?

Demedyuk told Reuters that Ukraine suspects the defacements were done by a hacker group known as UNC1151 and GhostWriter — an information-operations actor that has been linked to Belarusian intelligence. Belarus is a close ally of Russia.

But two sources close to the Ukrainian investigation say they have found no evidence yet linking the activity to Belarus and GhostWriter and that investigators are not in a position yet to attribute to any country or group.

Ghostwriter is known in part for targeting CMS systems to plant fabricated stories and content on media and other sites, according to Hultquist. They have also previously conducted operations designed to sow division between Ukraine and Poland, he notes.

Russia is an obvious suspect, given the current political tension and threat of invasion, as well as its history of conducting wiper operations. In 2016, systems in a wide spectrum of Ukrainian sectors were erased using a wiper attributed to Russia’s military intelligence, the GRU. And in 2017, Russia was behind the NotPetya worm that, similar to WhisperGate, targeted Ukraine and masqueraded as ransomware to overwrite files and cripple systems.

Microsoft wrote in its blog that so far it has found nothing that connects the WhisperGate wiper to any other hacker group it has tracked, and has not attributed it to any specific group or country.

Hultquist says that historically most defacements have been conducted by low-level hackers who leave political or patriotic messages on targeted sites. But government-sponsored actors have done them as well.

“Often times you’ll see a series of incidents that take a lot of different forms and they’re almost like a harassment campaign,” he said.

The Sony hack in 2014, attributed to North Korea, began with what looked like an extortion campaign — the hackers locked company computers and displayed a message threatening to leak data stolen from Sony unless the company paid an unspecified amount of money. At the same time, the hackers also wiped systems and then published company emails and sensitive documents online.

How Sophisticated Are These Incidents?

Hultquist says he would not characterize the wiper and defacement campaigns as a “massive cyberattack” because they lack scale, and the effects, so far, have been limited.

The attacks also are not sophisticated.

"Can anyone do this? The answer is yeah. A lightweight actor could do this,” he says.

But he notes that sophisticated actors don’t need to pull off sophisticated attacks if a simpler one achieves the intended result.

“It does make news. It is embarrassing, and it’s public,” he notes. “If the White House's social media accounts were compromised, it would be easy … to say anybody could have done that. But the public effect of that is substantial.”

The real question is, what is next?

“The kinds of things that I worry about are scaled-up attacks" that hit critical infrastructure or reverberate across multiple sectors and have widespread effect like NotPetya, he says. “That's when they can really do serious damage.”

In 2015, Russia took out power in part of Ukraine, and in 2016 it took out a transmission facility at the same time it launched the series of attacks that struck targets in the commercial and government sectors, including the national railway system and Ministry of Finance. So it has already demonstrated an ability to hit critical infrastructure and an interest in conducting multi-pronged and widespread operations.

Update: This story has been updated with a response from Kitsoft about the wiper and damage to its infrastructure. The intro has also been updated to indicate that the number of entities infected with the wiper were “several,” but the infections impacted dozens of systems belonging to those entities.

Update 1.18.22: This story has been updated with additional clarification from Kitsoft confirming that the company found the WhisperGate wiper on some of its systems.

Related:

Inside the Cunning, Unprecedented Hack of Ukraine’s Power Grid

The Ukrainian Power Grid Was Hacked Again

If you like this story, feel free to share with others.

If you’d like to receive future articles directly to your email in-box, you can also subscribe: