What It Means that the U.S. Is Conducting Offensive Cyber Operations Against Russia

Gen. Paul Nakasone's remarks this month about offensive operations against Russia caused a stir. But have people misinterpreted his words?

When General Paul Nakasone, commander of U.S. Cyber Command and director of the National Security Agency, told a reporter this month that the U.S. had engaged in offensive cyber operations against Russia in support of Ukraine, it caused a stir.

“We’ve conducted a series of operations across the full spectrum: offensive, defensive, [and] information operations,” Nakasone said, noting that the operations were lawful and conducted with the approval of the appropriate civilian authorities.

Nakasone didn’t elaborate on the kinds of operations he meant, but many people assumed he was referring to computer network attacks — operations designed to degrade, disrupt, or destroy a target. Cyberattacks of this nature would seem to contradict the White House's stated policy that the U.S. will not directly engage with Russia in its war against Ukraine. They could also potentially escalate the conflict, and pull the U.S. directly into war with Russia.

Days after Nakasone’s statement, Russia appeared to interpret Nakasone’s remarks as proof that the U.S. had shifted its policy. The foreign ministry warned the U.S. not to provoke Russia with cyberattacks or it would take “firm and resolute” retaliatory measures with potentially catastrophic results. “[T]here will be no winners in a direct cyber clash of states,” the ministry said.

But when asked during a White House press conference whether the offensive cyber operations contradicted the administration’s policy against direct involvement in the conflict, press secretary Karine Jean-Pierre said they didn’t.

“[W]e just don’t see it as such.… So, the answer is just simply: No,” she said.

She didn’t elaborate on the operations or explain why the administration thinks they don’t cross a line.

So how could both statements be true — that the US is engaging in cyber offensive operations, and the operations don’t contradict White House policy?

I spoke with three experts, who provided insight on the matter: Gary Corn was general counsel for U.S. Cyber Command from 2014 to 2019 and is now director of the Tech, Law and Security program at American University. Gary Brown was the first senior legal counsel for U.S. Cyber Command when it launched a decade ago and is currently associate dean of academics and professor of cyber law at National Defense University. The third expert is a current government official involved in decisions about U.S. cyber operations, who asked to remain anonymous because he’s not authorized to discuss such matters.

What Are Offensive Cyber Operations?

There was a lot of confusion around Nakasone’s comments because it was unclear what kinds of operations he was including in the term “offensive cyber operations,” also known as OCO in military parlance.

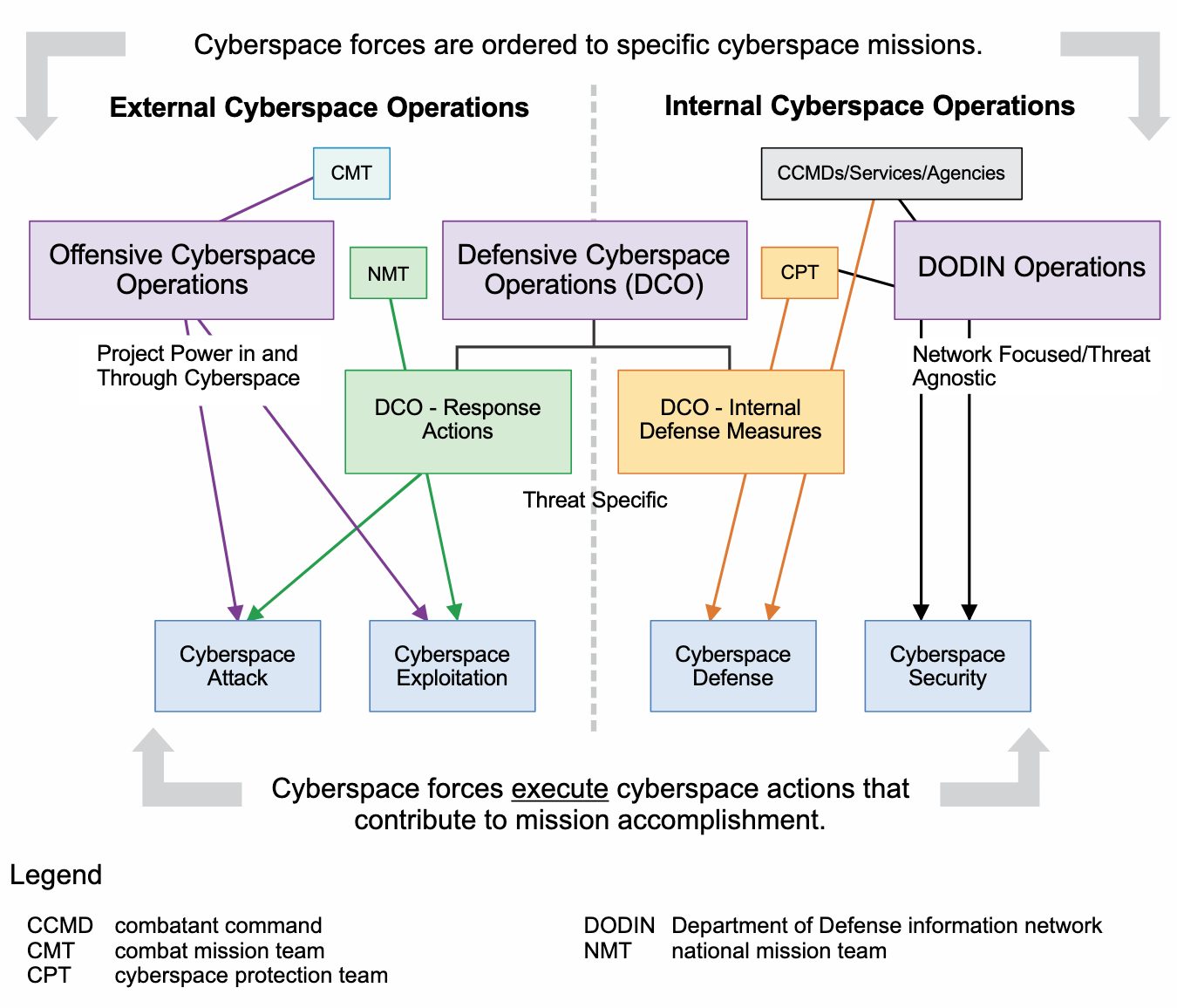

Under U.S. military doctrine — specifically Cyberspace Operations Joint Publication 3-12 — offensive cyber operations, broadly defined, are “missions intended to project power in and through foreign cyberspace” in support of combatant commanders or national objectives. The activity includes cyberattacks that either target the cyber capabilities of an adversary or cause “carefully controlled cascading effects” in the physical realm — for example, to affect weapon systems, command-and-control capabilities, or logistical operations. Some offensive cyber operations “may include actions that rise to the level of use of force” as it’s defined under international law.

But offensive operations also include cyber exploitation — operations conducted to collect intelligence. This includes, according to the DoD doctrine, military intelligence activities, information collection, and other actions that do not themselves “create cyberspace attack effects” but may be done in preparation for future military operations that produce such effects.

Gary Corn says this is different from the kind of intelligence collection done by the intelligence community for geopolitical purposes. This is reconnaissance to collect information about computer systems, networks and equipment in order to map their architecture or uncover vulnerabilities that might be used in a future cyberattack conducted by the U.S.

“It isn't necessarily altering the system in any way other than to be able to do the collection [of information],” he says.

Are Cyber Offensive Operations the Same as Hunt-Forward Operations?

No. Nakasone’s remarks created confusion about this because in the same interview where he mentioned offensive operations he also discussed “hunt forward” operations, leading some to believe these are the same thing.

Hunt-forward operations are not offensive operations. These involve threat-hunting activities inside U.S. government systems or inside the systems of a foreign government or entity — with their consent — to find hackers or evidence of a compromise in defense of networks. With regard to Ukraine, this can involve both remote assistance and on-site assistance to help Ukrainians uncover threats inside their networks. But such operations would not involve the U.S. hacking into Russian systems. And it wouldn’t be the first time the U.S. has engaged in hunt-forward operations outside the U.S.

“In the run-up to the 2018 midterms, those hunt-forward operations were done in Ukraine, Montenegro, and Northern Macedonia, as areas which are very much testing grounds for Russia's malicious cyber activities,” says Corn.

While conducting hunt-forward operations, the U.S. might discover Russian malware and implants that it then shares with Ukraine and other allies to develop defenses against them. Nakasone said in the interview that U.S. hunt-forward activities are “an effective way of protecting both America as well as allies” and have involved sharing information not only with Ukraine but also with commercial security firms. Before and since the invasion in February, security teams from Cisco, ESET, Mandiant, and Microsoft have been helping Ukraine defend and uncover threats to their networks, and the government’s hunt-forward operations would augment this activity.

Was Nakasone Talking About Attacks or Exploitation (Reconnaissance) When He Mentioned Offensive Operations?

It’s difficult to say. Nakasone perhaps intentionally left his comments vague, and both the White House and U.S. Cyber Command have declined to elaborate, simply referring reporters back to his oblique interview.

The operations may include a combination of reconnaissance and attacks intended to have an effect on systems as defined by military doctrine. But this doesn’t mean the U.S. has been destroying Russian systems. There is a vast spectrum of activity that can qualify as a cyberattack, from operations that produce only very subtle effects to ones that physically destroy equipment and potentially cross a line into a use of force.

All three experts say the U.S. is likely not engaging in the latter.

“I don’t know what [Gen. Nakasone] meant within that very broad range, [but] I doubt he was referring to operations that would constitute anything close to a use of force,” says Corn.

But this leaves a lot of options still available.

“The good thing about cyber is that it allows you to modulate [activity] to control your level of effect,” says the government official who asked to remain anonymous. “[T]here are ways that you can give support [to Ukraine] that don’t give Russia license to attack our country.”

And this is primarily what it comes down to when we’re talking about potentially escalatory activities — whether U.S. offensive cyber operations against Russia would qualify under international law as a use of force or an armed attack that could trigger Russia to respond in a way that pulls the U.S. into the conflict.

So What Kinds of Offensive Attacks Might the U.S. Be Conducting Against Russia?

The White House insists that none of the offensive cyber operations crosses the line into direct military engagement with Russia. Corn says he takes the White House at its word, but without knowing any details about the operations — what the targets were or the effects they had — it’s difficult to say if the operations risk pulling the U.S. into the conflict.

The administration has been very calculated in other types of support it has provided Ukraine to avoid being accused of direct engagement, and it’s likely to use the same considerations in the cyber realm.

What might the U.S. do that doesn’t risk being drawn into the conflict?

If Russia tried to defeat Ukrainian morale or conduct information operations against Ukraine, the U.S. could use a cyber operation to undermine or thwart their ability to send messages in some way, says the government official, and this wouldn't be a use of force, depending on the technique they used and the effect it had on Russian systems.

Corn offers a different example in which Cyber Command discovers the username and password for the administrator of a system being used to launch cyberattacks against Ukraine and gets into the system to change the password.

“[S]o now you've locked out the system user. You've had a disruption effect, but you haven't done anything to harm the system whatsoever,” he says. “That’s eons away from destroying [or] causing damage that would begin to implicate use-of-force questions. “

As for what kinds of activity would qualify as a use of force or armed attack or otherwise escalate the conflict, this is difficult to say because so many of the legal questions around cyber conflict and thresholds are still unresolved, the experts say. Even top legal minds that attempted to answer these questions in the Tallinn Manual — one of the primary resources for assessing cyber operations against international law — failed to agree on many scenarios.

“We could take down a network and as long as there is no kinetic effect and doesn’t cause injury, some could argue that would not be a use of force,” says the government official. “But this is an unsettled question…. We use these operations in a way that we avoid [crossing] the lines, but no one knows what the lines are. They’re forming every day.”

And each nation draws the lines differently.

“[If you’re] changing information, making a system slow down or stop operating temporarily or permanently… France would consider this a sovereign violation,” he notes. “But other nations would think it did not violate sovereignty and international law.”

What individual states say about how they interpret different actions and what they will tolerate matters a lot, says Corn.

“More and more states have been making pronouncements about their views on international law and cyber,” he notes. “But there’s still a lot of ambiguity on the edges of a lot of these rules.”

If a U.S. offensive cyber operation hasn’t killed anyone or done injury, an argument could be made that it’s not an armed attack, the government official says. But if a cyber operation renders equipment permanently inoperable, experts disagree on whether this is an armed attack.

The famous Stuxnet operation reportedly launched by the U.S. and Israel — that destroyed or disabled more than 1,000 centrifuges used in Iran’s nuclear program — was deemed an illegal use of force by the Tallinn Manual experts, but they disagreed on whether it qualified as an armed attack.

Brown says to get around this question about rendering an entire system inoperable, an operation could involve something more subtle like making sure specific malware launched by Russia doesn’t work, either by manipulating the code or diverting its path.

“The adversary doesn't necessarily know what's happening if malware doesn’t work, so they might think something is wrong with the software and not realize that someone reached into a server and made it not work,” he says. But if Russia learned that the malware was sabotaged, it could argue that this was direct engagement by the U.S.

If the U.S. were to take out or disrupt a Russian military system, not just a computer used for cyberattacks, the implications would be even more stark. Many have criticized the U.S. for refusing to impose or enforce a no-fly zone to defend Ukrainian airspace, on the grounds that it would bring the U.S. and European partners directly into the war. But if the U.S. disabled or disrupted Russian computer systems used to monitor and detect Ukrainian missiles launched against Russia or Russian forces in Ukraine, this could qualify as a use of force or armed attack, depending on how they conducted the operation.

Corn and Brown say it’s complicated.

“[There are] differing views by states on whether you need physical damage or injury to persons or just some loss of functionality,” says Corn.

Even if it were a use of force, this doesn’t make it unlawful, however, because Ukraine has the right of self defense and has made requests for assistance.

“And there's a collective component [to the right of self-defense under the UN Charter that would allow the U.S. to assist Ukraine],” he says.

He notes that the U.S. hasn’t said it’s engaging in collective self-defense for Ukraine, so this argument may be moot. But Corn says there is a separate question about whether such a level of coordinated support could still trigger the law of armed conflict, “making the U.S. a co-belligerent in the ongoing conflict.”

And in addition to all of this, Brown says an operation that disables or disrupts Russian air defenses would raise other concerns about potential escalation if it disabled Russia’s ability to detect and monitor attacks coming from other countries besides Ukraine, such as the U.S.

“You have to be very careful about taking away their ability to understand [incoming attacks], because we want them to know that we’re not launching [missiles] on them,” he says.

What About Assisting Ukraine with Cyberattacks It Conducts?

If the U.S. risks crossing a line by engaging in cyberattacks against Russia directly, could it instead provide Ukraine with intelligence that would help Ukraine launch cyberattacks against Russian systems?

“When you have an ongoing conflict, there is a risk that actions that directly enable one of the parties to conduct specific operations may make the enabling state a party to the conflict,” says Corn. “It can be a very fine line.”

It’s been reported that the U.S. provided Ukraine with intelligence that its military then used to sink the Russian warship Moskva and to kill a number of Russian generals. But the sensitivity around such intelligence-sharing was made apparent when the administration rushed to distance itself from Ukraine’s actions after the stories published. A spokeswoman for the National Security Council released a statement saying the intelligence was not provided to the Ukrainians “with the intent to kill Russian generals,” and other officials told reporters that the U.S. did not know that intelligence provided about the Moskva would be used by Ukraine to launch missiles against the ship.

Similarly in the cyber realm, if the U.S. were to provide Ukraine with information about vulnerabilities in Russian computers and networks that enabled Ukraine to launch attacks against those systems, it would potentially put the U.S. in a precarious position, especially because it might be difficult to claim that the U.S. provided the vulnerability information for any reason other than an attack.

Generally speaking, Corn says, “vulnerabilities are something that is pretty specific. Why would I provide the vulnerability if I didn't expect and anticipate that the Ukrainians would use that vulnerability to conduct some operational activity?”

Could Russia Retaliate Even if Cyber Operations Don’t Qualify as a Use of Force or Armed Attack?

Russia can do whatever it wants, though it has to weigh the legal, political and military ramifications of any response. Even if the U.S. conducts an operation that clearly qualifies as a use of force or an armed attack, Russia could decide it’s not in its interest to retaliate.

“There’s an absolutely huge political element to this,” Corn says.

He points to Iran’s lack of response to the Stuxnet attack.

“Most who look at [that operation] agree that it [caused] a level of damage and harm to the centrifuges of Iran that would rise to the level of a use of force. But Iran never said it was, and that’s a political decision Iran made,” he says.

See Also:

When Russia Helped the U.S. Nab Cybercriminals

Former NSA Hacker Describes Being Recruited for UAE Spy Program

The Spy Story that Spun a Tangled Web

Unmasking China’s State Hackers

If you like this story, feel free to share it with others.

If you’d like to receive future articles directly to your email in-box, you can subscribe for free or become a paid subscriber to help support my work if you find it valuable: