Unmasking China’s State Hackers

Intrusion Truth debuted in 2017, unmasking hackers working for the Chinese government. Five years later they’re still at it, while managing to keep their own identity a secret.

In 2017, an anonymous person or group calling themselves Intrusion Truth launched a bold initiative — a blog devoted to uncovering and publicly exposing the real names of Chinese state hackers allegedly responsible for stealing billions of dollars worth of trade secrets from Western companies to bolster China’s industries.

This so-called economic espionage violates the boundaries of what the U.S. considers to be acceptable spying, and in 2015 it prompted President Barack Obama to call out China for the activity, which the country has denied doing.

But rather than halt the theft, China simply created an apparatus to lend it plausible deniability that the state is behind the pilfering. Instead of cyber warriors in the People’s Liberation Army conducting the operations, China shifted the activity to the Ministry of State Security (MSS), a civilian intelligence agency more adept at stealth hacking, and created shell companies to hire civilian hackers to break into Western targets, according to Intrusion Truth.

“[T]here are ethical and moral boundaries which the Chinese continue to violate,” the group wrote in a blog post last year. “Utilising [sic] criminals to hack for the state’s bidding, and to do so to steal IP from hard-working companies provides an unfair advantage to prop up Chinese businesses.”

To call out the ruse, Intrusion Truth has made it a mission for the last five years to name and shame the actors, publishing more than two dozen blog posts doxxing the alleged hackers and the intelligence officers said to be directing their operations.

They expose names, social media accounts and even personal photos, while documenting the investigative steps taken to unmask the perpetrators. They’ve also relentlessly mocked the targets for making simple mistakes that left a digital trail to their identity, such as using the same email address to both register servers used in hacking operations and to post family photos on social media.

But the implications for those targeted by Intrusion Truth go beyond simply having their names exposed. In at least two cases, Chinese nationals identified by Intrusion Truth have been subsequently indicted by the U.S. Justice Department, creating the risk of arrest should they travel outside China.

Proponents of the group’s work say Intrusion Truth’s revelations about Chinese hackers are valuable for countering China’s claim that it doesn’t engage in economic espionage.

"I think it’s helpful…to have an organization…calling out Chinese…activity,” says Priscilla Moriuchi, a non-resident cybersecurity fellow at Harvard's Belfer Center who specializes in state-sponsored Asia Pacific hacking groups. “I think they have extremely solid analytic techniques, and they clearly have a lot of access to typical threat intelligence data and people who know what they’re doing. And largely, I think their reporting has been accurate.”

Ciaran Martin, former CEO of the UK’s National Cyber Security Centre, believes it forces accountability on actors who are otherwise protected by their government.

“So much of the harm we suffer is as a result of activity in countries where the people are in jurisdictions where we can't touch them,” he says. “And I think… specific attributions…to groups have made those groups sometimes feel uncomfortable — more in China and Iran than in Russia.”

Outing anonymous hackers can have a tactical effect, he says, by eroding trust within the hacking groups. If members can’t rely on one another to not make basic mistakes that could get them all caught — and potentially elicit anger from Chinese officials — it creates mistrust and tension.

“[I]t applies tactical pressure to them,” he says. “If it can prove to be tactically useful than why not do it?”

But there are ethical questions around doxxing people in China who haven’t been charged with a crime. Although some of the Chinese nationals Intrusion Truth exposed have been indicted, others have not — nor have they been sanctioned by the U.S. government.

There are also questions about some of the sources and methods the group uses to uncover identities. Most of the information they rely on is publicly available, but some of it is not. The group, for example, obtained credit card statements from an unnamed Bank of China source to identify one person, and they obtained Uber receipts to show another person commuting to and from an MSS building, appearing to confirm his work for the agency. Intrusion Truth didn’t say how the group obtained the receipts.

And there are concerns that publicly exposing another country’s state-sponsored hackers could prompt China to do the same with U.S. hackers working for the CIA, the National Security Agency or U.S. Cyber Command.

“I find it troubling because it seems uncontrolled when we start getting into the doxxing of operations and even operators, which starts hitting close to home,” says Joe Slowik, who leads threat intelligence operations for the security firm Gigamon and former information warfare officer in the U.S. Navy. “There’s always the question of where are the boundaries? lt also leads to the potential of doxxing the wrong person, which makes me very uncomfortable.”

Moriuchi, who used to work for the NSA, says mistakes the Chinese hackers make that allow them to be identified aren’t the kinds of mistakes NSA hackers make, but this doesn’t mean there isn’t a risk for U.S. government hackers.

“We don't have anyone at the NSA registering domains under their real name or phone number,” she said. “But is there information on people, on NSA operators, that could be used against them? Without a doubt.”

Intrusion Truth acknowledges there are risks that China could start hunting and exposing Western hackers in retaliation, but says the benefits outweigh this.

“Intrusion Truth’s primary goal is to expose the whole truth of Chinese state-sponsored hacking. We understand people might have a number of different concerns about what we do and how far we go,” a person representing the group wrote in an email interview with Zero Day. “But it is important for us and our community that we stick to that primary objective. We can’t let state-sponsored Chinese hackers act with impunity.” [To read the full interview with Intrusion Truth, visit this page.]

Zero Day examined the work Intrusion Truth has done over the last five years to analyze its methods, and spoke with a dozen security experts about the pros and cons of exposing nation-state hackers and the effect, if any, it has had on curbing China’s theft of trade secrets.

Who Is Behind Intrusion Truth?

Ever since Intrusion Truth launched there has been speculation about who is behind the group.

Some think it’s composed of rogue threat intelligence analysts working for security firms, who are frustrated by company policies that prohibit them from publicly identifying Chinese hackers under the company’s name. Others think the group is a security company in the U.S. or Europe publishing anonymously to avoid retaliation from China. (Intrusion Truth uses British spelling in blog posts, but this could be an affectation to misdirect suspicion about who is behind the operation.) Still others think the group is a cutout for a Western government.

The timing of indictments following revelations made by Intrusion Truth raises questions about the group’s possible connections to the Justice Department as well as motivations for the group’s work: Does Intrusion Truth coordinate with U.S. prosecutors on the indictments? Does the government use Intrusion Truth to publicly out individuals for which there isn’t enough evidence to indict?

Intrusion Truth told Zero Day that the group is composed of and consults “a global network of anonymous contributors” from a variety of backgrounds whose identities are sometimes unknown even to each other.

“[W]e don’t always know their real-life identity, sometimes just their online persona,” the group said in an email.

This doesn’t preclude that Intrusion Truth is a single individual who solicits help from a loose network of experts or that this person or members of the network are affiliated with, or collaborate with, a Western government.

Mei Danowski, a threat analyst who has followed Intrusion Truth’s work closely, told Zero Day she thinks the group may be engaging in parallel construction — where an intelligence agency obtains information through classified means and passes it to another entity to build a trail to the same information using public, non-classified sources to keep the classified methods and sources secret. Danowski believes someone may be providing Intrusion Truth with the names of the Chinese hackers and tasking them with building a public trail to those identities so the Justice Department can indict them.

Asked about coordination with the government, Intrusion Truth initially replied obliquely: “We know the impact of Intrusion Truth is real. It is not surprising to us that governments are interested in our work and read what we have to say.” But the person responding on behalf of the group appeared to deny parallel construction in a followup response, writing that the “Intrusion Truth community guides and informs all the work we do, including what Chinese hackers we go after.”

Exposing APT 3 Hackers

Intrusion Truth says they were first inspired to publicly out Chinese hackers by the work of an anonymous cybercrime blogger named Cyb3rsleuth, who was partly responsible in 2013 for exposing an assistant professor at China’s PLA Engineering University — reportedly a training center for electronic intelligence — for allegedly being a spy. Cyb3rSleuth claimed in an interview with Bloomberg at the time that he was 33 years old and the operator of “an India-based computer intelligence company.” He stopped publishing his blog in January 2016, about a year before Intrusion Truth launched their project.

Intrusion Truth’s work debuted in the spring of 2017 in what appeared to be a response to a news article published by the Washington Free Beacon months earlier. The Free Beacon’s November 2016 story revealed that an internal Pentagon intelligence report had identified the Guangzhou Bo Yu Information Technology Company in China — also known as Boyusec — as a contractor or front company for the MSS.

Boyusec, together with Chinese tech giant Huawei, produced security systems for telecom networks that the Pentagon suspected were embedded with backdoors for the MSS to siphon traffic, according to the Free Beacon. Curious about the company, Intrusion Truth began investigating it and found that two of Boyusec’s top shareholders had registered domains used for command-and-control servers in APT 3 hacking operations. [APT stands for Advanced Persistent Threat and refers to hacking groups, generally state-sponsored, with advanced skills. To distinguish groups, security researchers number them APT 1, APT 2, etc.]

APT 3, also known as Gothic Panda and Buckeye in the security community, has been active since 2010 and is accused, among other things, of breaking into tech, aerospace, defense, and telecom companies in the U.S. and U.K. It’s also, according to Intrusion Truth, an arm of the MSS intelligence agency.

When the group published their first blog posts in May 2017 identifying the two shareholders — Wu Yingzhuo and Dong Hao — and their connection to APT 3, the reaction was immediate. Boyusec’s website went offline, and a week later the security firm Recorded Future published its own blog post corroborating the findings with additional information about Boyusec’s connection to the MSS and APT 3.

Moriuchi, who worked for Recorded Future at the time, was behind the company’s blog post. She had just joined the company and told Zero Day she had been preparing to publish her own findings about APT 3’s connections to the MSS when Intrusion Truth trumped her.

“They had a different set of data, [but] I thought, whoa, this is awesome…. I kind of had another side to what they were doing,” she said.

The timing of Recorded Future’s post made some people in the security community suspect Moriuchi or Recorded Future were behind Intrusion Truth. But Moriuchi denies this.

“It’s not me. I don’t know who it is,” Moriuchi told Zero Day, adding that whoever is behind the group “is highly skilled and has a breadth of skills that are not typically resident in one person.”

An analyst who currently works for Recorded Future but who asked to remain anonymous to speak freely about the issue, said neither he nor anyone he knows at Recorded Future has worked with Intrusion Truth.

The revelation from Intrusion Truth marked the first time an APT group was conclusively linked to the MSS. Previously, China’s state-sponsored hacking operations were attributed primarily to the People’s Liberation Army. But in late 2015, after Obama called out President Jinping Xi for China’s economic espionage and the two reached an “understanding” about the activity, security firms reported seeing a drop in such operations from China. In reality, they had simply shifted to the MSS, which took some time to build up infrastructure for the operations. By the time President Trump took office in 2017, China had reportedly resumed and even accelerated its intellectual property theft.

Six months after Intrusion Truth exposed the Boyusec shareholders, the U.S. Justice Department announced charges against the two men, along with a third colleague, Xia Lei. It was the first indictment of Chinese state hackers since 2014, when DoJ had last indicted members of the PLA.

The three Boyusec associates were charged with computer hacking and theft of trade secrets for allegedly breaching the email account of a prominent economist with Moody’s Analytics in 2011; for hacking and stealing about 400 gigabytes of data from Siemens energy, technology and transportation divisions in 2015; and for hacking the GPS firm Trimble in 2015 and 2016 to steal information about a product Trimble was developing for mobile devices.

About a week before the Justice Department announced its charges, Boyusec was de-registered from a Chinese government-run database, suggesting the company had been dissolved.

"Boyusec disappeared into the shadows without making any effort to contact us or to refute any of the conclusions of our analysis," Intrusion Truth wrote at the time. “These were not the actions of innocent individuals.”

It was proof, Intrusion Truth said, that “one of the biggest hacking threats to Western companies” could be “completely silenced by shining a light on its activities and exposing the identities of those behind the group to the world.”

But Danowski, who gave a presentation about Intrusion Truth last year at the Cyberwarcon conference in Washington, DC, expresses doubt that Boyusec disappeared altogether. She told Zero Day that she found job advertisements for the company in February 2018, two months after the indictments, and believes the company may have simply begun to keep a lower profile.

Take Two: Exposing APT 10

Intrusion Truth went silent for a year after its reports about APT 3. When the group published again in August 2018, it was to expose individuals and companies involved in a different Chinese hacking group, APT 10.

APT 10 has been blamed for Operation Cloud Hopper, a series of intrusions into more than 45 tech companies and IT managed service providers, and for stealing hundreds of gigabytes of sensitive data across multiple industries — tech, aviation, space and satellite, manufacturing, pharmaceutical, oil and gas, and communications.

Intrusion Truth connected APT 10 to a regional office of the MSS in Tianjin and to three Chinese nationals — Zheng Yanbin, Gao Qiang and Zhang Shilong. Zhang, they said, worked for a shell company in Tianjin called Huaying Haitai Science and Technology Development that conducted the APT 10 hacking operations.

Four months after identifying the men, the Justice Department indicted Zhang, citing his connection to Huaying Haitai, and two years later, the European Union announced sanctions against Gao Qiang, Zhang Shilong and Huaying Haitai — the first EU sanctions for cyber-espionage.

Intrusion Truth’s posts since then have exposed other APT groups and have also revealed a distinct pattern in how the MSS operates. The spy agency first tasks a regional MSS office in places like Tianjin and Guangdong with forming shell companies or co-opting existing tech or security firms. Then the companies recruit civilian hackers, usually from local universities.

Often the shell companies are easy to spot because they have little presence on the internet and share the same contact information or office address in job listings. One company apparently used a computer security professor — a former member of the PLA according to Intrusion Truth — to recruit hackers and acquire new tools and techniques. Someone claiming to be a student of the professor wrote online that the teacher was looking to pay the equivalent of $30,000-$76,000 to anyone with innovative ways to crack passwords. “Believe it or not,” the student wrote, “our teacher has a lot of money.”

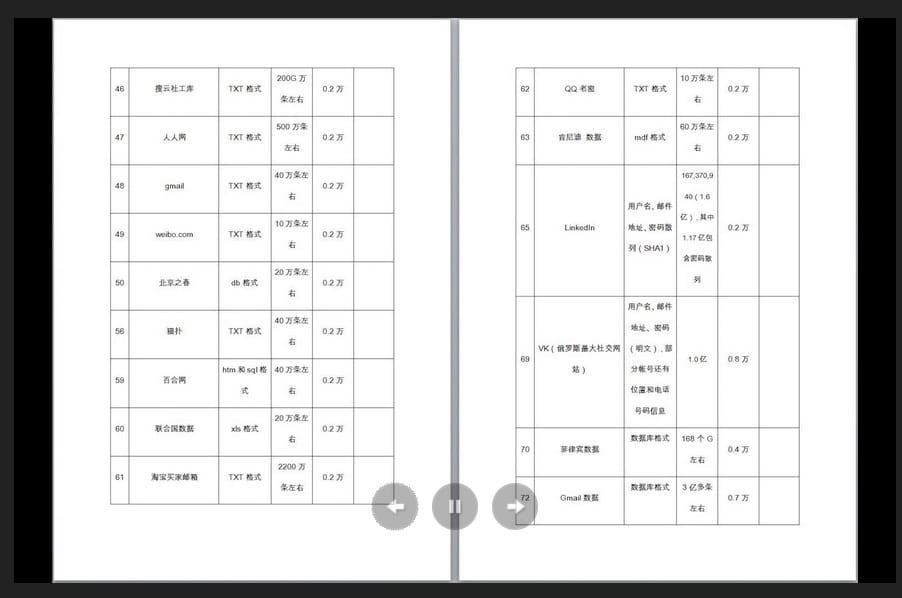

In shifting hacking operations from the PLA to the MSS, China might have thought it gained plausible deniability for its operations, but it also learned that there are potential drawbacks to using civilian hackers for state-run operations: they can be less disciplined and controllable than military-trained hackers and may engage in the occasional side hustle. According to a DoJ indictment, Gao Li allegedly attempted to extort one espionage victim in 2017, demanding $15,000 in cryptocurrency to not leak data stolen from them. Intrusion Truth also says members of another group, APT 17, allegedly circulated a price list in hacker forums for data it swiped from Western and China-based hacking targets. Some APT groups have even re-used state-sponsored malware to steal virtual currencies and tokens in video games.

But the biggest drawback to using civilian hackers might be their lack of commitment to separating work life from personal life. Intrusion Truth was able to identify many of the APT hackers because of their re-use of email addresses for professional and personal purposes. An MSS officer named Zhao Jianfei was identified because he sent zero-day exploits to two indicted hackers using the same email address he used to receive credit card statements from the Bank of China. He also used a variation of that email address as his user name on Facebook, according to Intrusion Truth.

On the Hunt

Intrusion Truth’s investigations begin in a number of ways but usually they start with a tip from a reader or with an email address published in reports written by security firms.

“We receive tips on a weekly basis from around the world on Chinese cyber activity and the actors suspected of being behind it,” the group says.

The group then uses a variety of methods to track targets, including sifting through data stolen from Chinese companies and leaked online. A leak of usernames from the Tencent Weibo QQ instant messaging service aided a couple of investigations, and in another case a handy list of public toilets helped them identify the address of an intelligence agency office in Hainan.

“[T]he Chinese internet is huge and awash with lots of information which can help our investigations,” Intrusion Truth told Zero Day. “Accessing it is easier than most people think. The more you dig behind the Chinese firewall, the more you find.”

Intrusion Truth, or a member of its network, appears to be fluent in Mandarin and has a practiced ability to dig deeply into Chinese-language university sites, hacking forums and social media accounts to uncover resumes, academic papers, wedding photos, email addresses and online aliases.

But although most of the information Intrusion Truth uses is open source, some evidence appears to come from non-public sources. In one case, they were able to determine that two individuals working for different companies were associates after a “source with access to such information” provided information revealing the two men had sat next to each other on three flights in 2016.

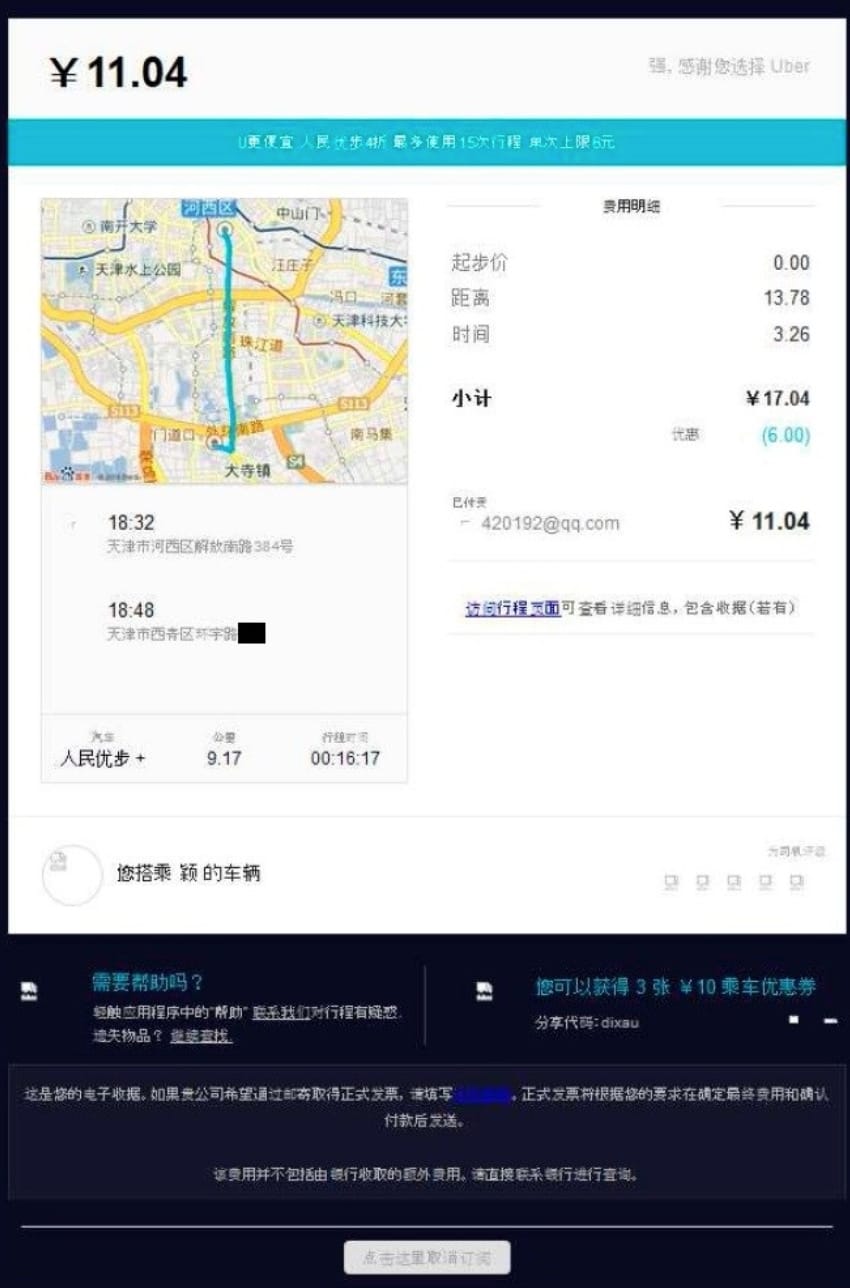

In another case, they obtained Uber receipts purporting to show their target commuting to and from an MSS building.

The investigation began with an email address — zhengyanbin8@gmail.com — that had been used to register domains for APT 10 operations. Intrusion Truth pulled threads for a year collaborating with unnamed threat intelligence analysts, which led them to identify three individuals — Gao Qiang, Zheng Yanbin, and Zhang Shilong.

They were able to connect Gao Qiang to the MSS through the Uber receipts. One receipt, for a user named “Qiang,” showed the rider traveling from the headquarters of the Tianjin State Security Bureau — an arm of the MSS — to a residential neighborhood. A second Uber receipt showed the same user, named Pig this time but using the same email address, traveling repeatedly between the two locations.

Research into the identity of a different MSS officer was aided by credit card statements that Intrusion Truth says came from a source connected to the Bank of China. The investigation began when the Justice Department indicted two Chinese hackers in July 2020 for allegedly stealing hundreds of millions of dollars in intellectual property from companies, including ones conducting COVID-19 research and testing. The Justice Department mentioned an intelligence officer — MSS Officer 1 — who it said was affiliated with the Guangdong State Security Department (GSSD), a branch of the MSS in Guangdong.

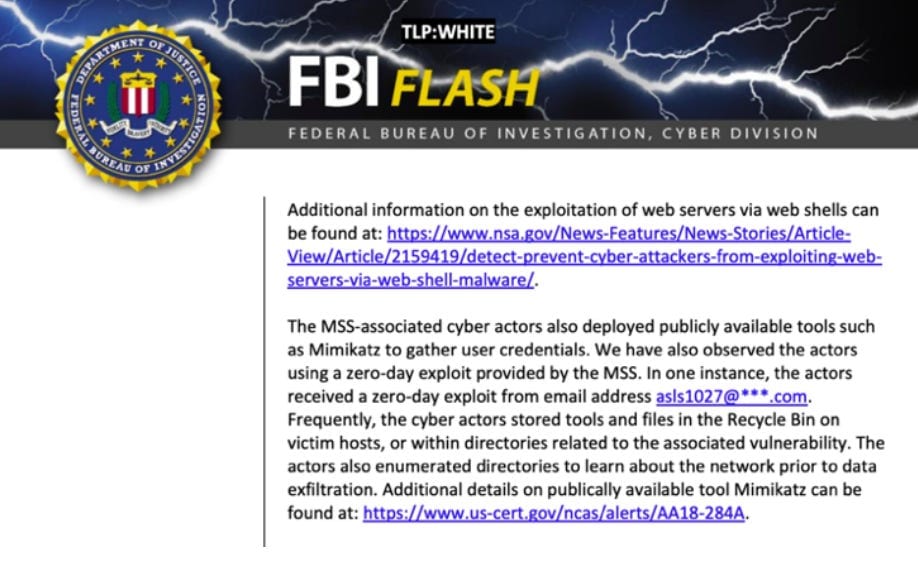

Intrusion Truth set out to identify the officer using two clues: the address for a research facility that the indictment said was a shell company for the GSSD, and an email address used by MSS Officer 1 to send zero-day exploits to the two indicted hackers. The second half of the email address was redacted in an FBI alert, but it began with “asls1027”.

The address for the research facility was on Upper Nonglin Road in Guangdong, so Intrusion Truth asked its network of contributors for anything related to the address. A “trusted source with connections to the Bank of China” produced credit card statements that were purportedly sent by the bank to a person named Zhao Jianfei at the research facility’s address. A second bank statement was emailed to asls1027@hotmail.com.

In another investigation that also began with an email address — dxy0015@163.com — Intrusion Truth was able to connect the address to Ding Xiaoyang, an intelligence officer overseeing APT 40 operations, after someone in its network of collaborators accessed a frequent flyer account tied to that email. The email address had evidently been among stolen credentials that hackers had leaked online, and Intrusion Truth’s collaborator evidently used the credential to gain unauthorized access to Ding's account and learn his name.

Intrusion Truth taunted Ding in their post. "Our thanks…go out to Mr Ding for not changing his password after it had been leaked online.”

Intrusion Truth isn’t clear about who gained access to the account, but ordinarily this would be illegal in the U.S. if not done by law enforcement, and it’s generally not condoned by the security community.

“We are bound by U.S. laws,” says Ben Read, director of cyber-espionage analysis at the security firm Mandiant, who says his company would not access accounts using leaked credentials. But he says others in the community might consider this “a gray area.”

Critics say that without oversight, there's a risk that Intrusion Truth could identify the wrong person. But the group said it takes care to corroborate tips supplied to it and to get the facts right.

“We are rigorous in our verification of information,” the spokesperson wrote in an email. “We always publish in good conscience, knowing that we have tried our best to make sure we are revealing ‘the whole truth.’”

The person also pointed out that their work “is often independently corroborated by other threat hunters” after they publish their findings, such as Recorded Future did in 2017.

But there are questions about whether such corroborations are truly independent. The Intrusion Truth spokesperson noted that some of the people who assist with the group’s investigations are anonymous. It’s possible then that some of these people also work for companies that have subsequently corroborated Intrusion Truth’s findings, making it only appear that the companies reached the same conclusion about a hacker’s identity independent from Intrusion Truth.

How Effective is Intrusion Truth’s Work?

Little happens to China-based hackers who get publicly identified. Those who are sanctioned might suffer financial setbacks, and those who are indicted might feel restrictions against travel, but as long as they don’t travel to or through countries with extradition agreements with the U.S., they don’t have to worry about being nabbed by law enforcement.

Whether simply naming and shaming hackers is effective is open to debate.

A former U.S. national security official, who asked to remain anonymous to speak freely about the issue, said there’s value in outing people who aren’t indicted.

“You may not have enough evidence to bring charges, but you want to undermine their ability to operate — in the same way you kick spies out of the U.S.,” he told Zero Day. “We do that publicly to embarrass the other nation and to call out that we know who your spies are.”

The Recorded Future analyst who asked to remain anonymous says the revelations are valuable because they get people talking about the problem of economic espionage. He also says he has learned information from Intrusion Truth that he didn’t know before. “We certainly have used it to our advantage to help identify and track some activity,” he says.

But Mandiant’s Read says that while the information can contribute to a big-picture understanding of the threats, it doesn’t really help security teams defend networks, and it’s not going to stop hackers in China from stealing intellectual property. It does, however, put them on notice that they might get caught “and people will know” what they did, he notes. This, at the very least, can impose cost on them — that is, force them to expend more effort to conceal their identity.

Dmitri Alperovitch, co-founder and chairman of Silverado Policy Accelerator, says the shock of being publicly outed used to be more effective years ago when he did it with a member of a Chinese hacking group called Night Dragon in 2011 while working as vice president of threat research for the security firm McAfee. But it’s become less effective over time. Alperovitch didn’t name the person in China in 2011, but he did name the city where the person was based and revealed that he owned a hosting company. He also quoted a line from the company's marketing literature that would have left the owner little doubt that the description was referring to him.

“When [these exposures first occurred] the adversaries were not expecting them, and they were in huge shock,'“ he says. “I think it did have an effect of ‘Oh my god, somehow they discovered us. But I think as they’ve seen over the years that nothing really happens to them [after being exposed], it becomes probably more of a badge of honor.”

Nonetheless, there could be value in making state-sponsored hackers think twice about their ability to travel freely outside China. And the exposure of one hacker can potentially lead others to make different life choices.

“Chinese hackers do have a choice about their occupation,” Intrusion Truth notes. “There is a booming tech industry in China — and around the world — where these hackers could really put their skills to better use.”

The group says it has no plans to slow down and is already lining up new revelations to release this year.

“[W]e’re currently working collaboratively with a couple of members of our community on an investigation to try and identify a long-standing Chinese hacker…. We will see how successful we are.”

To read a complete interview with Intrusion Truth, go to:

Intrusion Truth: Five Years of Naming and Shaming China’s Spies

See Also:

When Russia Helped the U.S. Nab Cybercriminals

Former NSA Hacker Describes Being Recruited for UAE Spy Program