Sophisticated StripedFly Spy Platform Masqueraded for Years as Crypto Miner

Malware discovered in 2017 was long classified as a crypto miner. But researchers at Kaspersky Lab say it's actually part of a sophisticated spy platform that has infected more than a million victims.

When researchers at Kaspersky Lab first discovered the StripedFly malware on customer systems in August 2017, they weren’t impressed. They believed it was a crypto miner crafted by cybercriminals, and not a very successful one at that. It made just $10 in 2017 mining Monero cryptocurrency, and about $500 in 2018.

But when new samples of the miner started showing up last year on customer machines all over the world — not the sort of victims that usually get infected with cryptocurrency miners, but government agencies and large commercial organizations — Kaspersky researchers decided to investigate it more closely.

Sergey Lozhkin, principal security researcher at Kaspersky’s Global Research and Analysis Team, says Kaspersky software initially detected something malicious in the WININIT.EXE process on customer computers, which was triggered by code sequences they had earlier seen in malware used by the NSA’s Equation Group hackers. This caused them to investigate further and connect it back to the 2017 discoveries of the cryptocurrency miner.

But as they examined the miner and these new infections closely, they discovered the miner was actually a cover for a sophisticated spy platform that has infected more than one million victims around the world since 2017.

The cryptocurrency miner is just one component of a large and complex platform that the researchers call StripedFly. The platform is designed for use on both Windows and Linux-based systems and has numerous plug-ins that give the attackers broad spying functionality. Such functionality is common in nation-state spying platforms but not in criminal malware, which is what the researchers originally took the cryptocurrency miner to be.

The spy components include ones for harvesting credentials from infected machines; for siphoning .PDFs, videos, databases and other valuable files; grabbing screenshots; and recording conversations through an infected system’s microphone. The platform also has an updating function that lets the attackers push out new versions of it whenever Windows and Linux operating systems get updated. The malware gets pushed out from encrypted archives stored on GitLab, GitHub, and Bitbucket.

But there are three additional things that are notable about StripedFly: it uses a remarkable custom-coded TOR client to transmit communication and siphoned data between infected systems and the attackers’ command and control server. It has a ransomware component that has infected a small subset of victims, including ones in Taiwan. And it uses a custom EternalBlue exploit as the initial vector to get the spyware onto victim machines.

Eternal Blue was an infamous Windows exploit created and used by an NSA hacking group known as the Equation Group — the name Kaspersky gave the group in 2015 when it discovered tools made by the group. Equation Group was responsible for the Stuxnet tool that sabotaged Iran’s nuclear program between 2007-2010 as well as a host of sophisticated spy tools discovered by Kaspersky.

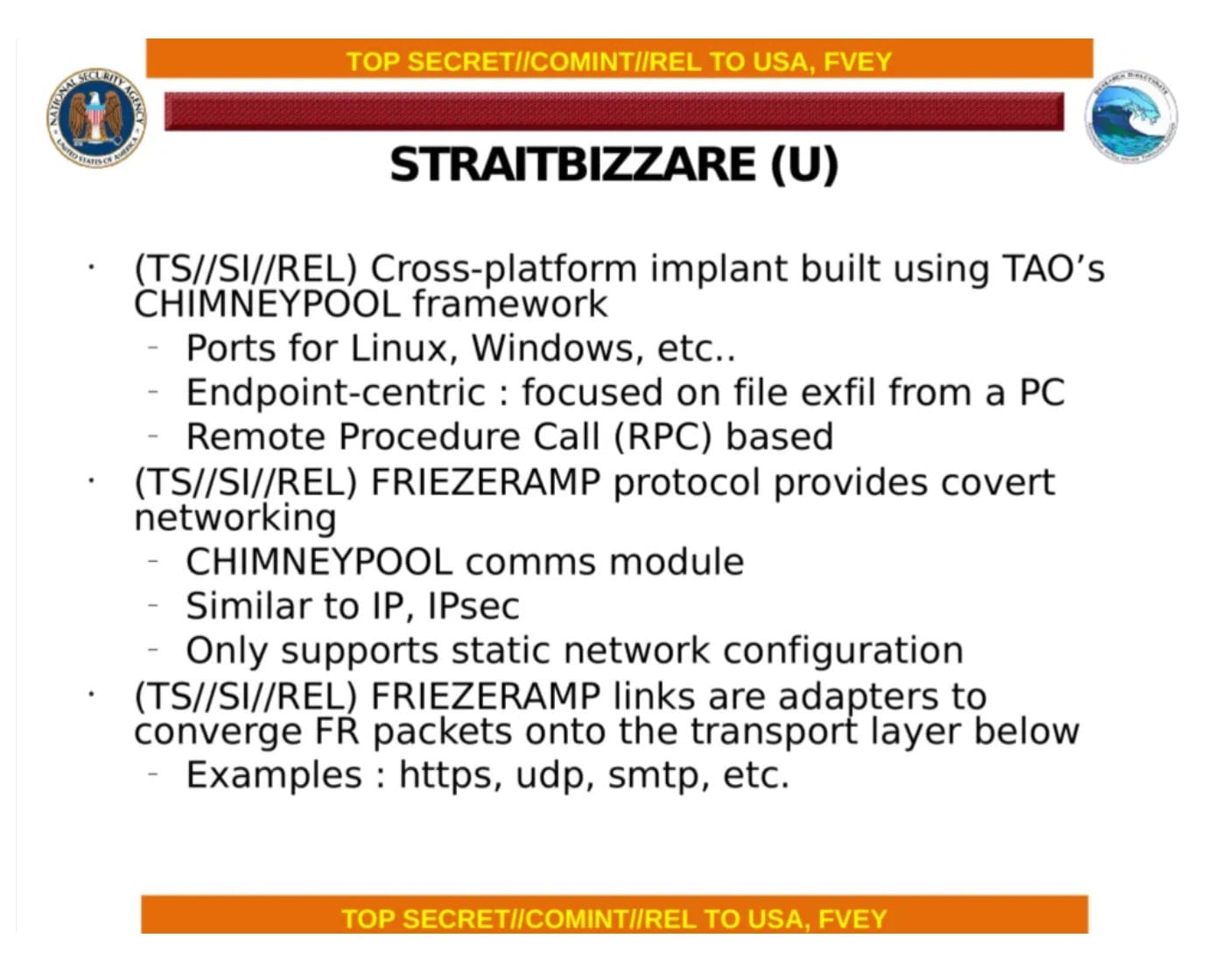

StripedFly, Lozhkin says, has some similarities to Equation Group malware and has coding style and practices that resemble an NSA implant known as STRAITBIZARRE that was exposed in the Edward Snowden leaks in 2013. But despite the similarities, the researchers say there is “no direct evidence that they are related” or that StripedFly is an NSA platform.

Nonetheless, “the amount of effort invested in creating this framework is truly remarkable, and its unveiling was quite astonishing,” says Lozhkin, whose team published information about StripedFly in a private technical report last year, but plans to present their findings publicly for the first time on Thursday at the company’s Security Analyst Summit in Thailand.

It’s worth looking at three of the most interesting aspects of StripedFly.

The Custom TOR Client

The TOR client is a remarkable addition to the platform, Lozhkin says, because it’s not based on any known implementation of TOR. Instead the attackers, who he describes as really skilled coders, created a lightweight version that’s missing a lot of TOR functionality, such as the use of routing, relays and exit nodes.

They may have done this for security reasons if they suspected existing TOR clients might contain backdoors or vulnerabilities that would allow someone to intercept traffic. TOR exit nodes are also a security risk since they can be used to siphon documents transmitted through the TOR network.

TOR, or The Onion Router, uses distributed computing to transmit data and documents in a secure and private manner among a network of computers — many operated by people who volunteer their systems for use in the network. The originating computer and destination computers are not known by the computers in between, and the data that gets transmitted is encrypted. Each node or computer in the network can only see the node from which it received traffic, and it has to peel off a layer of encryption to determine the next node to which it must send the traffic. The last node through which the traffic travels, however, decrypts the traffic before sending it to its final destination. Someone operating that last node, known as an exit node, can see the communication passing through it.

Sometimes hackers use the TOR network to siphon data that they steal from victim computers. This puts the data at risk of being seen and intercepted by anyone operating an exit node through which it passes.

Wikileaks was reportedly launched with documents siphoned from a TOR exit node in 2006. An activist working with the organization was running a TOR exit node and siphoned more than a million documents as they passed through his server. The documents were believed to have been stolen from victims by Chinese hackers or spies who used TOR to transmit the purloined documents. The hackers were believed to be part of the China-based hacking group known as GhostNet, which was responsible for hacking embassies, foreign ministries and activist groups in more than 100 countries —but primarily in Taiwan and other parts of South and Southeast Asia.

Did the StripedFly attackers learn from this and build their own TOR client to avoid passing their stolen data through nodes belonging to someone else? Possibly. Either way, “such an approach is by no means common among APT and crimeware developers, and this notable example underscores the sophistication of this malware against the background of many others,” the researchers write in their blog post about StripedFly. “Its functional complexity and elegance [reinforces] its classification as a highly advanced threat.”

The ThunderCrypt Ransomware Component

The ransomware component is probably the oddest part of the StripedFly platform. It appeared in an early version of the malware and has left the researchers baffled about who is behind the platform — nation-state actors conducting spy operations and using the cryptocurrency miner and ransomware as a cover to hide their espionage; nation-state actors moonlighting as ransomware operators to earn money on the side; cybercriminals hacking for profit and also doing espionage-for-hire operations?

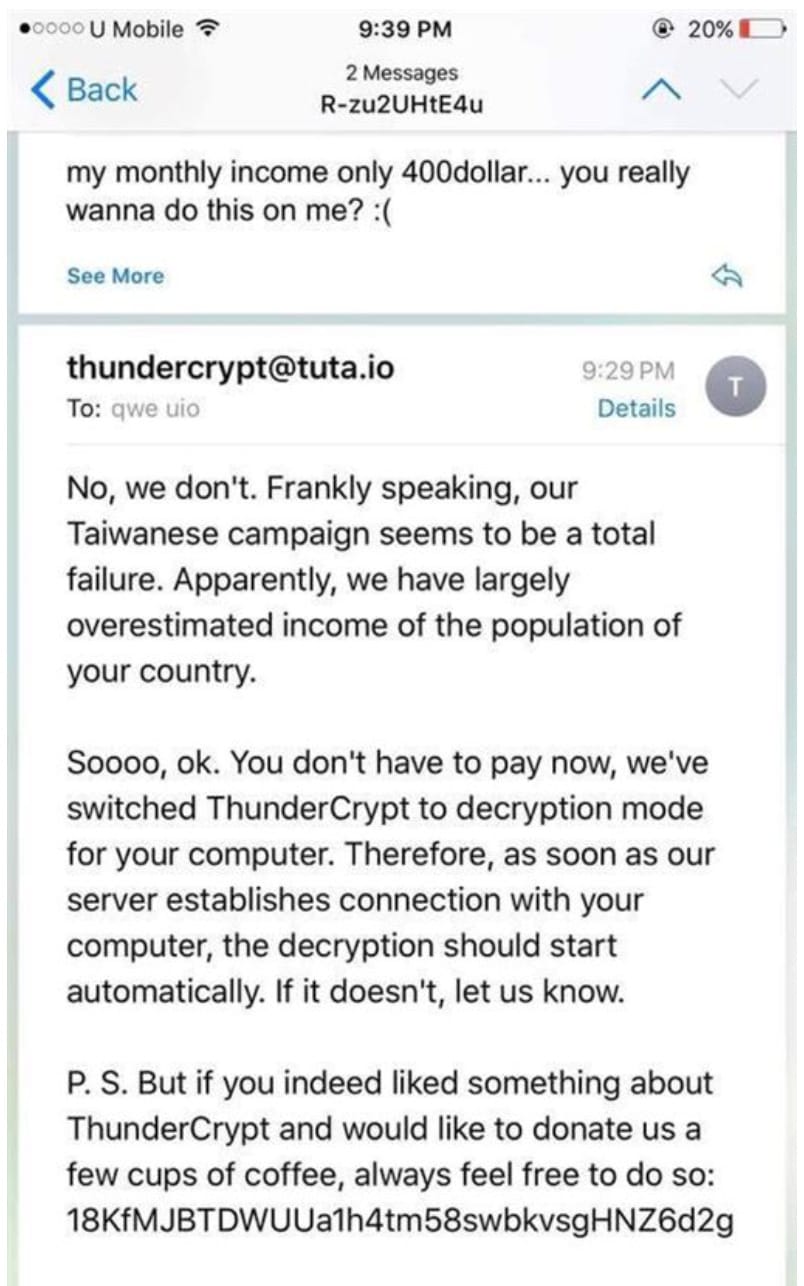

The ransomware component — named ThunderCrypt — was first detected by Kaspersky in April 2017, though Kaspersky had no idea at the time that it was part of a larger operation. A month after Kaspersky detected it, the ransomware appeared in a news story in Taiwan when a Taiwanese citizen got infected with it and pleaded with his attackers to release his files without paying the 0.345 bitcoin ransom. He told them he only earned the equivalent of $400 a month and therefore couldn’t afford the ransom, and the attackers — uncharacteristically for ransomware actors — took pity on him and said they had overestimated the income of people in Taiwan.

“Frankly speaking, our Taiwanese campaign seems to be a total failure,” the attackers wrote back to him in well-constructed English. “Apparently we have largely overestimated income of the population of your country.”

They decrypted the files on his computer but also suggested a tip might be in order to help them buy a couple cups of coffee.

The ransomware infected fewer than 1,000 people around the world, Lozhkin says. Why would someone put ransomware in an espionage tool? Lozhkin can only speculate. He thinks it might be intended to be used as a wiper or destruction tool — perhaps as a kind of kill switch. If the spying operation gets caught and they want to destroy evidence on infected systems they can lock up the files and systems so the victim can’t do a forensic investigation. Because the malware doesn’t include a cryptocurrency wallet to pay a ransom — the victim has to contact the ransomware operators directly — the Kaspersky researchers aren’t able to determine if anyone has ever paid a ransom to the attackers.

The ransomware component and the crypto-mining component are the outliers in StripedFly, since they aren’t typical of nation-state operations. The crypto-mining module, however, is what helped the malware avoid detection for so long because it led researchers to believe this was the malware’s sole functionality.

Ironically, however, it’s also what got the Kaspersky researchers to look more closely at the malware and discover its true espionage purpose. Lozhkin says the malware contained code that was encrypted and unencrypted, and the only unencrypted strings were related to the cryptocurrency mining function.

“That was one of the things that attracted our attention — why there is something that is encrypted?… So we looked deeper,” he says.

The EternalBlue Connection

The use of the EternalBlue exploit to get StripedFly onto systems is interesting — especially for the timeline around its use.

Two years after Kaspersky exposed the Equation Group’s work in 2015, a number of their tools, including EternalBlue, got stolen and leaked online by an anonymous group known as the Shadow Brokers.

The ShadowBrokers revealed publicly in August 2016 that they had obtained NSA files and planned to sell them, but didn’t leak the actual EternalBlue code at that time. NSA figured out that they likely had the EternalBlue code in their possession and contacted Microsoft to get the vulnerability it exploited patched. Microsoft released a patch for the Windows vulnerability in March 2017, and a month later on April 14 ShadowBrokers leaked the EternalBlue exploit code online.

In May, North Korean hackers used the EternalBlue exploit to spread the WannaCry worm, and in June, Russian hackers used it to spread the NotPetya worm.

But notably, Chinese hackers had already been using the EternalBlue exploit a year before ShadowBrokers published it. A group called BuckEye, which has been associated with China’s Ministry of Security Services or MSS, was using an EternalBlue exploit of their own in March 2016 in spying campaigns, as well as another tool that was a copycat of an NSA tool called DoublePulsar. Researchers believed the hackers had likely found the tools on a machine in China or elsewhere that was infected them and created copycats of the exploits after reverse-engineering them and learning what vulnerabilities they were exploiting.

Around the same time in April 2016 that BuckEye was using their EternalBlue exploit, the StripedFly actors were incorporating their EternalBlue exploit into their spy platform, four months before ShadowBrokers announced that it possessed NSA tools and planned to leak them. They continued to use it for StripedFly years after Microsoft issued a patch in March 2017 to fix the vulnerability EternalBlue exploited, because many system owners never applied the patch.

The timing is intriguing, but it’s not clear if there’s anything connection between BuckEye and StripedFly or any other known hacking groups.

The question remains who is behind the enigmatic StripedFly.

“I’ve seen many kinds of [nation-state] code for the last five years and … they all try to mimic each other,” he says. “They implement false flags; they implement different kinds of code taken from various [nation-state actors]. They even use code creation similarities — patterns that we saw in the past. So attribution these days is a very complicated thing.”

See Also:

Mysterious New Hacking Group Leaves Researchers Baffled

How North Korea Workers Tricked U.S. Companies Into Hiring Them

Thank you for reading. If you found this article useful or interesting, feel free to share it with others.

Zero Day is a reader-supported publication. You can support my work by becoming a paid subscriber; or if you prefer, you can subscribe for free:

You can also give a gift subscription to someone else: