Pegasus Spyware: How It Works and What It Collects

An NSO document leaked to the internet reveals how the Pegasus spyware - sold to intelligence and law enforcement agencies around the world - can be used to spy on targeted mobile phones.

Revelations about Pegasus surveillance software continue to come a week after a consortium of 17 media outlets began publishing stories about the spy tool.

To recap, the media outlets that participated in the Pegasus Project consortium, reported that the software sold to governments for monitoring terrorists and criminals has been abused by repressive regimes with bad human rights records to spy on journalists, human-rights activists and their families and associates — contrary to claims by these governments and the company that makes the surveillance tool.

The stories were based in part on a leaked list of 50,000 phone numbers believed to have been chosen for surveillance by governments using the Pegasus software. But they also were backed by forensic analysis on several dozen of those phones conducted by Amnesty International. That analysis found that of 67 phones on the list that were forensically examined, 23 of those showed signs of a successful Pegasus infection, and 14 showed signs of at least an attempted infection.

NSO Group, the Israeli company that sells the software, has denied that its spy tool has been misused by governments and accuses the media outlets of basing their stories on false assumptions. But the company also announced last week that it had temporarily blocked several customers from using Pegasus while it investigates the accusations.

Two new stories published this week would seem to support the findings of the Pegasus consortium. In the first, government investigators in France, conducting their own analysis independent of Amnesty International and the consortium of media outlets, found evidence that the surveillance software had been used to target the mobile phones of three journalists in that country, including a senior staff member at the French television channel France 24.

And British human rights activist and attorney, David Haigh, also found that his mobile phone had been hacked using Pegasus, following a forensic examination of the phone by Amnesty International. Haigh’s phone number was not on the list of 50,000 numbers and had not been part of the original Amnesty investigation.

Haigh presumably was targeted because he had been assisting Dubai’s Princess Latifa bint Mohammed al-Maktoum in her campaign to flee her family and country — whom she accused of imprisoning her in her home — when his phone was targeted with the Pegasus software in August 2020.

French journalist Lénaïg Bredoux, whose phone was also allegedly targeted, told The Guardian that “it’s extremely unpleasant to think that one is being spied on, that photos of your husband and children, your friends – who are all collateral victims – are being looked at; that there is no space in which you can escape…. As journalists, what is even more worrying is that sources and contacts may have been compromised, that these are violations not just of your privacy and private life, but of the freedom of the press.”

Most people will not be a target of this particular surveillance tool — which is sold to government intelligence agencies and law enforcement. But it’s representative of other tools utilized by criminal and nation-state hackers, who don’t limit their use to tracking terrorists, criminals, journalists, activists, and princesses. They target anyone who might have valuable information they want.

So what exactly does Pegasus software do?

What is Pegasus?

As noted, Pegasus is made by the NSO Group, a company based in Israel that claims the software was developed by “veterans of intelligence and law enforcement agencies.” The Washington Post has a good piece describing how the company entered the surveillance space after initially launching as something entirely different — NSO helped phone carriers troubleshoot the mobile phones of their customers by sending the phones an SMS link that gave the carriers remote access to phones. You can see why law enforcement agencies might have thought this could be useful for other purposes and therefore urged NSO to develop surveillance software.

The Pegasus tool gives NSO clients powerful abilities to remotely and surreptitiously extract stored and real-time data from phones without tipping off the user that their device is spilling its secrets.

Why use Pegasus? It gives governments a way around encryption. If targets are using Signal or WhatsApp or any other application that encrypts communication end-to-end (from the sender’s device to the recipient’s device), this prevents anyone from intercepting that protected communication. Similarly, mobile phone protocols like 3G and 4G also use encryption to protect mobile voice communications from most types of interception. So a spy tool that sits on a user’s phone or iPad and records conversations in real-time or intercepts written communication before its encrypted and leaves the device — or after it arrives to the device and gets decrypted — has a natural appeal for spies and law enforcement.

What are its capabilities?

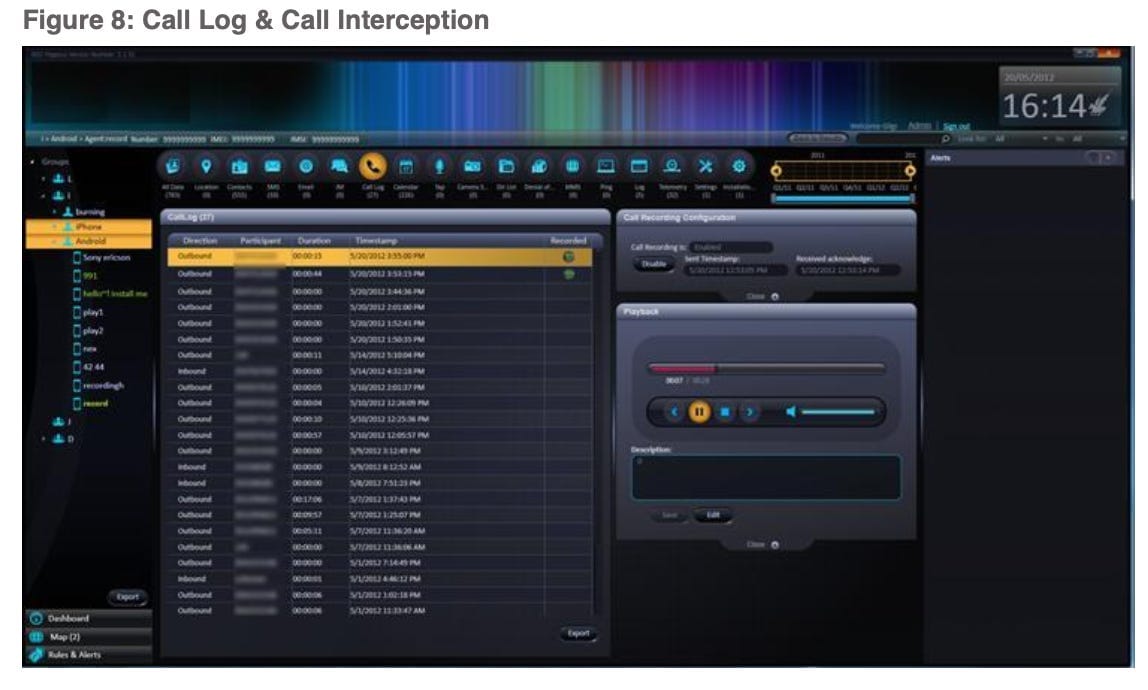

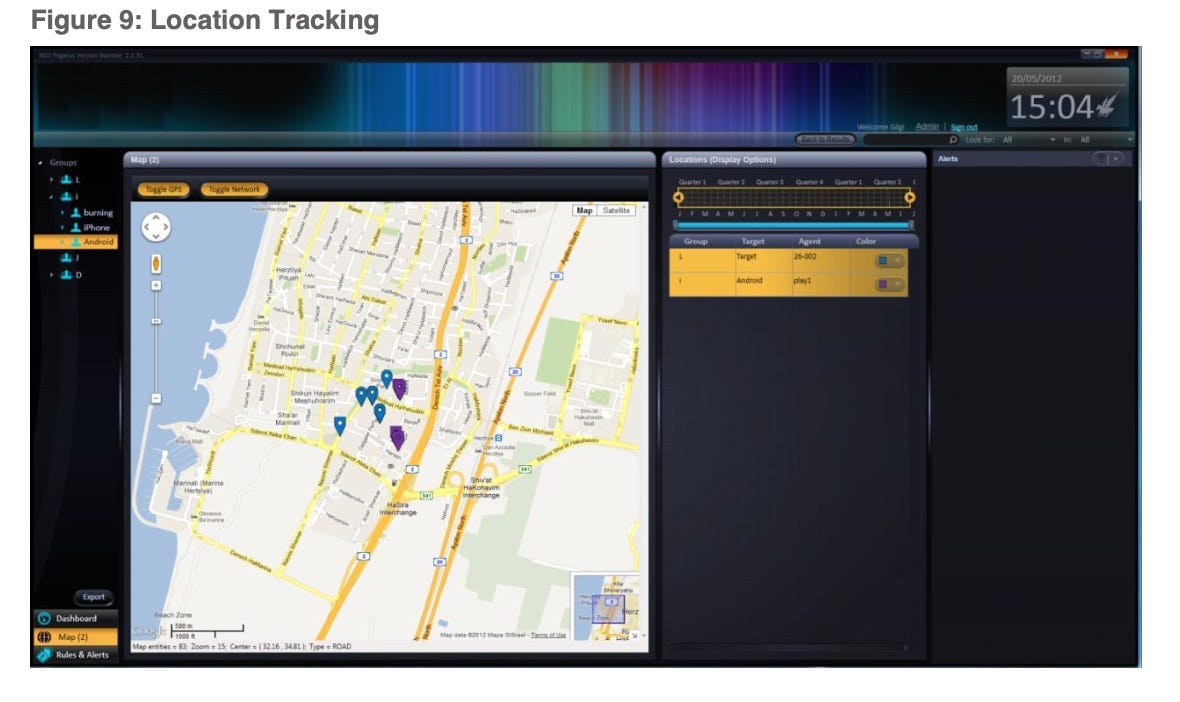

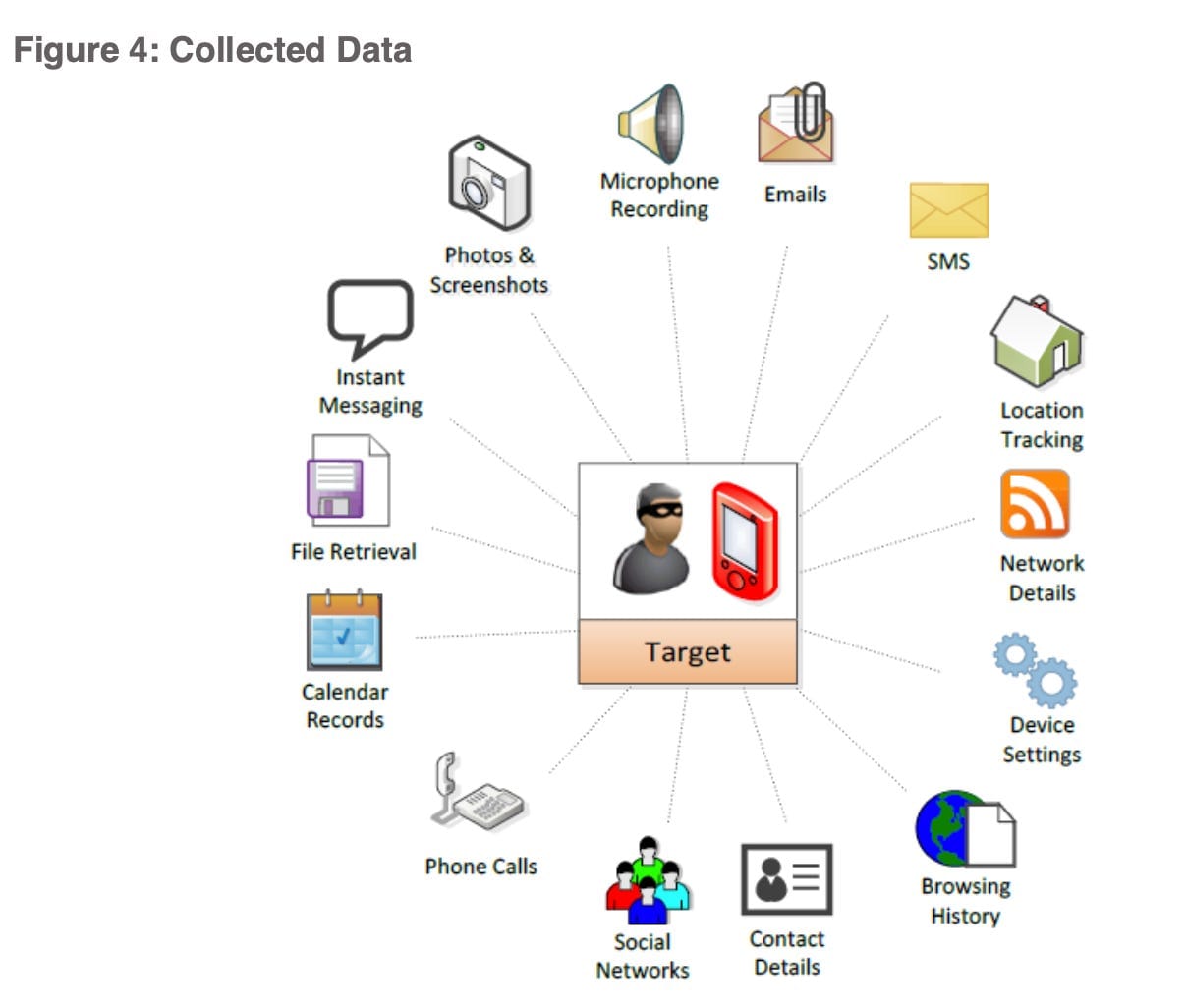

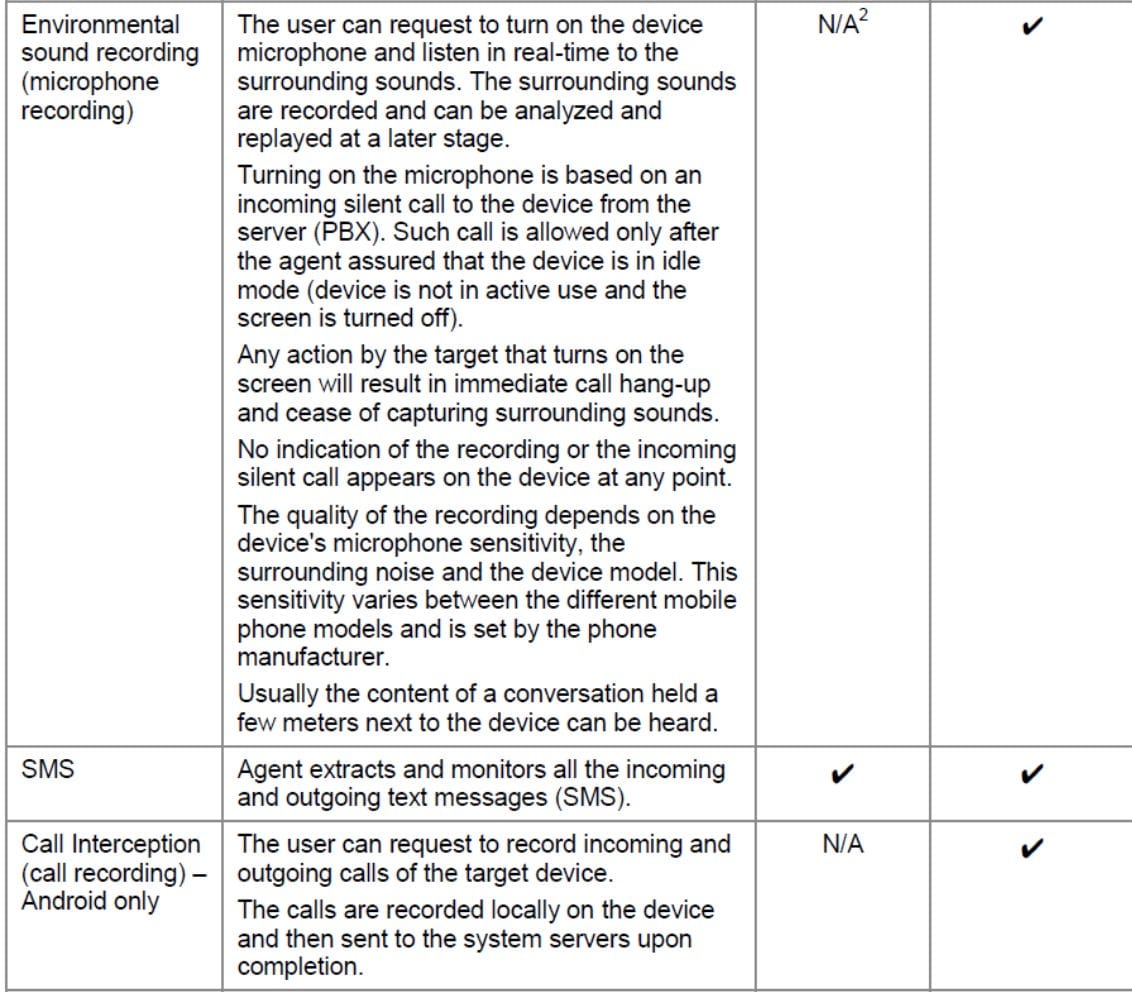

So how does Pegasus work and what does it capture? Based on a Pegasus marketing brochure that was leaked online and appears to have been created in 2016, Pegasus can collect usernames and passwords — for unlocking the device itself or for gaining access to the target’s email account or other accounts like Skype, WhatsApp, Twitter, and Facebook. It can extract all data stored on the phone, including the user’s database of contacts, text messages sent and received, emails, photos, voice memos, calendar entries, call history, and browsing history. It can also activate the phone’s camera to grab images of the user or their surroundings, and it can activate the microphone to eavesdrop and record voice and VoIP calls in real time or monitor conversations occurring in the vicinity of a phone — for example, while it sits atop a restaurant table or the desk in a worker’s office. And it can collect GPS data from the phone to track the user’s location and movements on a map.

Pegasus customers can either collect all data from a target’s phone or configure it to retrieve only specific types of information or only when specific events occur. For example, customers can request the spyware to send an alert and record information only when the target is communicating with a specific phone or the target arrives at a specific location or travels to a geographical area.

“Instead of just waiting for information to arrive, hoping this is the information you were looking for, the operator actively retrieves important information from the device, getting the exact information he was looking for,” the marketing literature states.

How does Pegasus transmit the collected data?

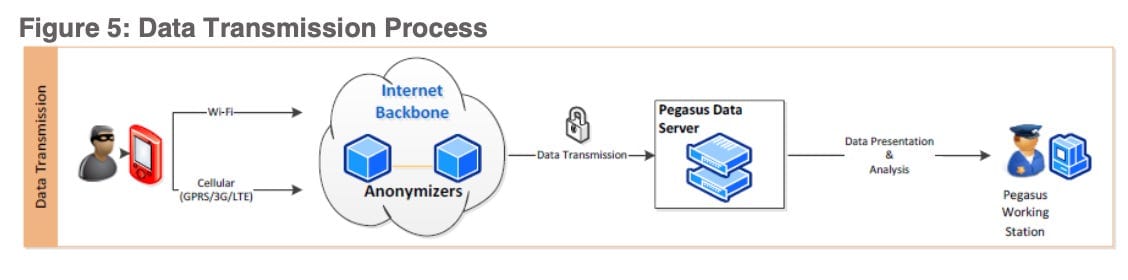

Pegasus copies the information, compresses it and encrypts it (using AES 128-bit), then transmits it from the phone to a command and control server set up on the Pegasus customer’s network. It sends the data to these servers at regular intervals or when the device is turned on and has internet connectivity.

Until the data gets transmitted, NSO says it’s stored in a “hidden and encrypted buffer” that is configured to hold no more than 5 percent of the device’s available space. If the device has 1GB of free space, for example, the buffer can store up to 50 MB of data before it starts to delete the oldest data.

The data is transmitted via WiFi when available, or via cellular networks. Though if the target is traveling in areas where expensive roaming charges might apply for transmitting data, WiFi is used, or the transmissions will stop altogether until the target is in a WiFi zone again.

The compressed data usually takes up only a few hundred bytes so that it won’t affect the performance of the device or, if it’s sent via cellular networks, won’t show up as excess data usage on a victim’s phone plan.

NSO Group says the transmitted data passes through anonymizing nodes located in different parts of the world in order to mask where the data is going and prevent a victim, or anyone else intercepting the encrypted data, from tracing the spying activity to a government agency’s network. NSO says anonymizing nodes are set up for each customer so that only data collected from phones targeted for surveillance by that particular customer gets passed through the nodes.

How does Pegasus infect mobile phones?

Pegasus can be installed on mobile phones in one of three ways: physically, remotely via a text message or email, remotely via a silent message pushed to the phone. Physical infection occurs when someone has direct access to a mobile phone they want to infect. The company says it takes less than five minutes to install the spy tool on a device.

For remote infections, a phishing text message or email is sent to the user — sometimes spoofed to make it appear to come from a trusted family member or friend — along with a link. When the user clicks on the link, it takes their phone’s browser to a malicious page where Pegasus gets downloaded silently in the background without the user knowing it. All that’s required is the target’s phone number or email address, and the system sends the message automatically. The system provides customers with examples for crafting a text message or email that is likely to entice the user to click on the malicious link.

Perhaps most alarming, Pegasus can be delivered to phones using a no-click or zero-click exploit that doesn’t require the recipient to click on anything to be infected. This more insidious method involves sending a silent iMessage in the background to the user’s phone so the user won’t see a text message on their screen. The customer creates iCloud accounts to send the messages. "The installation is totally silent and invisible and cannot be prevented by the target,” Pegasus says in its marketing literature.

Where the victim is unlikely to click on a malicious link, Pegasus can also be injected into a phone using a stingray (also known as a rogue cell tower or rogue base station) in the vicinity of the phone — doing what is called a network-injection attack or man-in-the-middle attack. This can be useful when a target’s phone number is unknown. The Pegasus literature isn’t clear about how this would be used, but police or intelligence agencies can use a stingray that causes any phone in its vicinity to connect to the stingray instead of to a legitimate cell tower. The stingray can then direct the device to a malicious web page where Pegasis is silently downloaded to it. In 2019, Business Insider photographed a device being sold by NSO Group at a surveillance tradeshow in Paris that appeared to be a rogue base station or stingray. NSO had the device sitting in the back of a van at the tradeshow, to demonstrate its portability. A 2019 report by Amnesty indicates that a stingray was likely used to infect the phone of Moroccan human rights defender Maati Monjib with Pegasus.

Pegasus is able to infect phones — even iPhones and iPads with the latest security patches installed — because NSO Group uses zero-day exploits that attack software vulnerabilities that are yet unknown to the phone maker and are therefore unpatched. In its recent analysis of Pegasus, Amnesty International found that Pegasus was using exploits that were successful against iPhones running iOS 14.6 software, which was the latest version of Apple’s mobile phone operating system at the time of Amnesty’s analysis. Each time Apple patches its operating system, NSO Group has been able to find or purchase new zero-day exploits attacking software vulnerabilities in different parts of the iPhone operating system, keeping one or two steps ahead of Apple’s patches.

Can Pegasus be detected on a phone or iPad?

According to NSO Group, no. According to Amnesty International and other groups that have conducted forensic investigations of infected devices, yes.

“Detecting [Pegasus] is almost impossible,” the company’s marketing brochure states. “The Pegasus agent is installed at the kernel level of the device, well concealed and is untraceable by antivirus and antispy software.” And once the spyware is uninstalled from a device “it leaves no traces whatsoever or indications it was ever existed there,” the company claims.

Pegasus also includes a self-destruct mechanism that can be activated remotely. “In cases where a great probability of exposing the [software] exists, a self-destruct mechanism is automatically being activated and the agent is uninstalled. [The software] can be once again installed at a later time…. In cases where the [software] is not responding and did not communicate with the servers for a long time, the [software] will automatically uninstall itself to prevent being exposed or misused,” the company’s brochure states.

But Amnesty International’s technical report describes many artifacts left behind on mobile devices by Pegasus that have helped them identify phones that were infected or were targeted with an attempted infection.

Amnesty has also released a tool for detecting Pegasus on devices. It’s designed primarily for detecting Pegasus on iPhones, because Android phones don’t preserve the kind of evidence needed to detect Pegasus. But Amnesty says the tool can still help detect some Pegasus artifacts on Android phones. The Verge has a good explainer for using the tool.

Claudio Guarnieri, head of Amnesty International's Security Lab, which conducted the forensic investigations for the Pegasus Project, says phone developers make it difficult to audit their devices to find spyware and has called on phone makers to rectify this.

“It wasn't thanks to any dark wizardry [that] NSO kept secret,” Guarnieri wrote in his newsletter this week, “but because of the difficulty to audit mobile devices why Pegasus for so long enjoyed an undeserved reputation of being undetectable, and why for so long technologists gave up even trying to check activists' phones….

“[C]ollecting forensic evidence is harder than it should be,” Guarnieri continued. “While we developed a decent process for [detecting Pegasus on] iPhones, we still wander in the dark on most Android devices. Manufacturers ought to explore more opportunities to enable users to securely gather more diagnostic information useful to validate the integrity of their devices and identify potential traces of compromise. What we have now is not enough.”

See also:

The NSO “Surveillance List”: What It Is and What It Isn’t

If you liked this article or found it useful, fee free to share it:

If you’d like to receive other articles like this directly to your inbox, subscribe here: