Anatomy of a $2 Million Darkside Ransomware Breach

Days before the Darkside ransomware creators formally launched their business with a press release last August, a U.S. victim was already preparing to pay them a $2 million ransom.

One of the first known cases involving Darkside ransomware occurred in late August 2020.

The victim, reportedly Brookfield Residential Properties, a Calgary-based home builder and land developer for residences in Canada and the U.S., evidently refused to pay the ransom and instead restored their data and systems from backups. For this brazen act, the hackers victim-shamed Brookfield on their Darkside blog on August 21, 2020.

Another company, hit with the Darkside ransomware around the same time as Brookfield, did pay the ransom — $2 million, according to Stephen Boyce, an incident responder who led the team that investigated the infection. For this reason the public has never learned of the breach.

“Our victim paid, so they were not publicly named and/or shamed,” says Boyce.

Boyce is a former FBI investigator in the bureau’s digital media exploitation unit who was working at the time for a Virginia-based security company called Crypsis. He says the victim was a privately held U.S.-based holding company, which he declined to name. The firm — an international conglomerate — may have been one of Darkside’s early beta victims, used to test the gang’s methods as well as the efficacy of their ransomware and decryption tools (the tool given to victims to unlock their computers and data after they pay a ransom).

The Darkside ransomware locked about 5,000 of the company’s computers and servers — including data backups that they’d kept online — and also spread to five of the holding company’s subsidiaries.

What happened next provides a stark illustration of the calculations companies make when deciding to pay a ransom.

In both cases Brookfield and the holding company didn’t just lose access to data, they also lost control of it. With Brookfield, the hackers claimed they swiped 200 gigabytes of data before locking the company’s systems with the Darkside ransomware — this included finance and payroll records, business plans and employee files. They threatened to publish the data if the company didn't pay the ransom. But Brookfield downplayed the incident, telling reporters the hackers only got a “limited subset of files” related to employees, and declined to confirm the incident involved ransomware.

In the case of the U.S. holding company, the hackers stole 100 gigabytes of data — “indiscriminate grabbing,” as Boyce called it — and made the same threats. Despite the fact that the company had a second, offline backup of its data that wasn’t affected by the ransomware — and therefore they didn’t need to pay the hackers — the holding company forked over the $2 million.

“From a business-continuity perspective,” and calculations about the maximum amount of time the business could afford to be down — restoring backed-up data can take weeks for a large firm and months for a company to return to normal — the holding company decided it would be more expedient to just pay the ransom, Boyce says, and get quick access to the files they needed. They paid it the way many victims do — through their ransomware insurance.

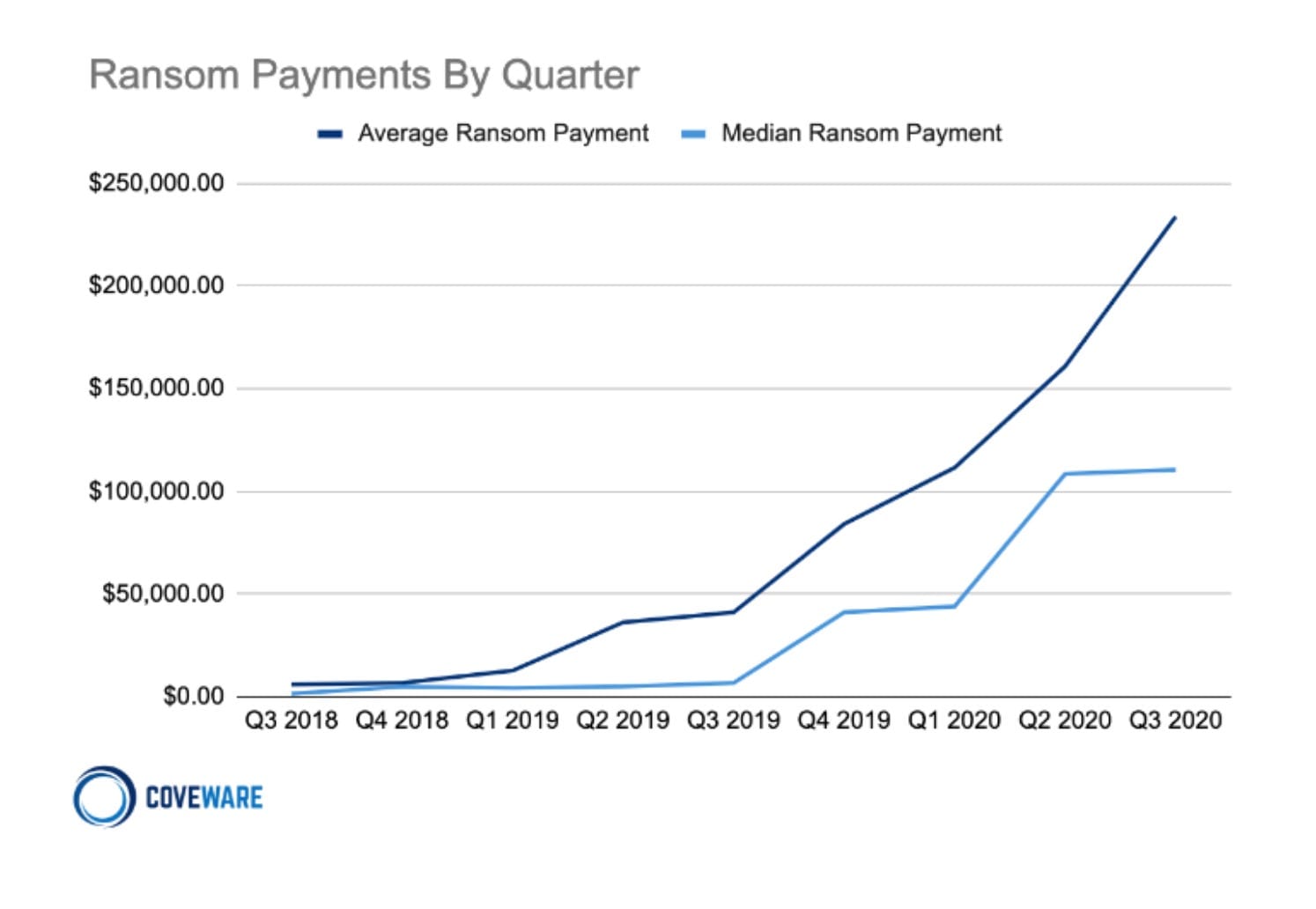

According to a chart published last year by Coveware, a company that negotiates ransoms on behalf of victims, the holding company paid well above the average rate for ransomware extortion, which last year was about $234,000.

Dark Beginnings

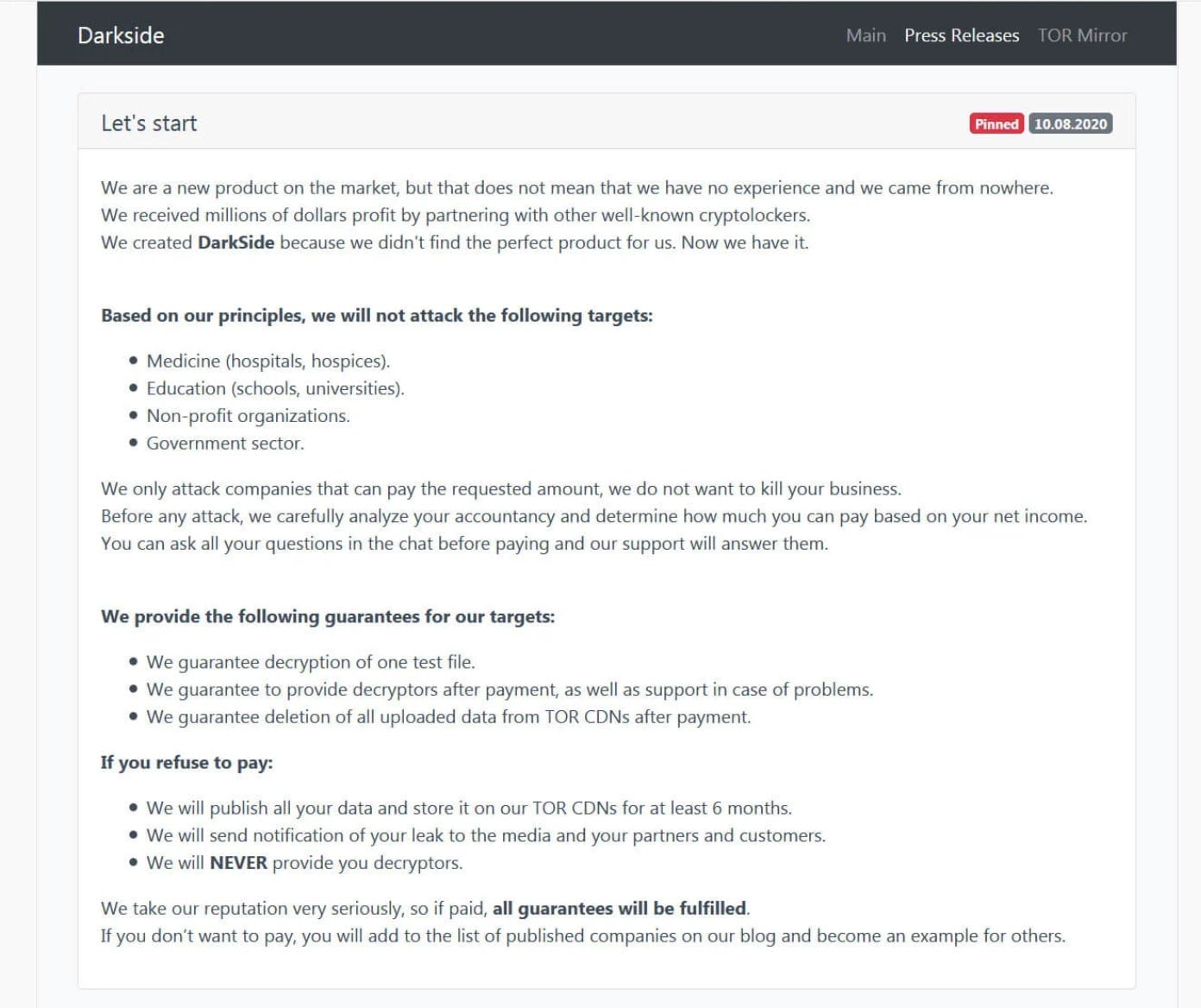

The developers behind Darkside first went public with their new ransomware tool on August 10, 2020, when they announced it with a press release. This was three days after the Darkside ransomware struck the U.S. holding company’s systems.

“We are a new product on the market, but that does not mean that we have no experience and we came from nowhere,” the person or group behind the ransomware code wrote in their release. “We created Darkside because we didn’t find the perfect product for us. Now we have it.”

The group is believed to have prior experience with other ransomware groups and is also believed to be Russian or East European since they advertise on Russian-speaking forums, and their code looks at the language configuration of a system and won’t deploy if the system appears to belong to someone from Russia, Ukraine, Belarus or other former Soviet-bloc nations.

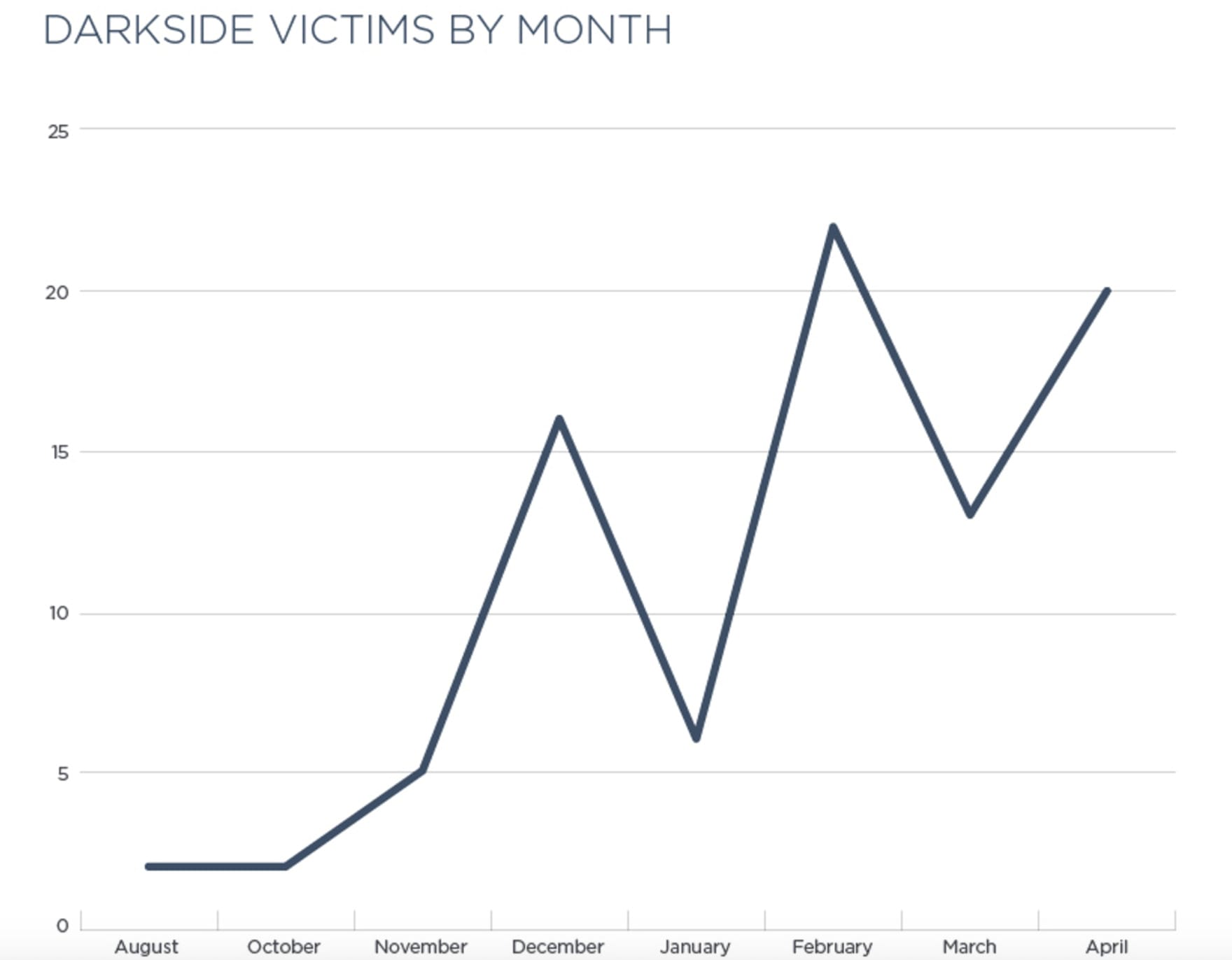

Darkside began as just a ransomware tool, but over time it morphed into ransomware-as-a-service (RaaS), meaning the developers behind the code don’t necessarily conduct the intrusions that use the tool. Instead they provide their malicious tools and services to other criminal affiliates or partners, who then use them to infect and extort victims, giving a percentage of the paid ransoms to the Darkside developers. According to Mandiant, the developers take a 25 percent cut for ransoms less than $500,000 and a 10 percent cut for ones exceeding $5 million.

The services provided in exchange for this fee include infrastructure for communicating with infected systems and storing data stolen from victims, as well as a “customer help center” with online chat and a phone line for desperate victims needing to communicate with their attackers.

More recently they have added new extortion features for their criminal affiliates to increase the pressure on victims: a call service that will phone victims and pressure them into paying the ransom and a DDoS feature for attacking the web sites of victims not inclined to pay, according to journalist Brian Krebs. And last month, in an announcement about hacking publicly traded companies listed on stock exchanges, the ransomware hackers indicated they’d be willing to sell advance information about victims to investors who want to short a company's stock before the hackers publicly announce the company has been breached and publish their stolen data online.

The group began advertising their ransomware-as-a service business three months after the holding company was compromised, according to the security firms Intel 471 and Mandiant when a Russian-speaking actor using the name "darksupp" advertised on two Russian-language criminal forums that he was “looking for partners” to launch an affiliate model for his business. Soon after, the Darkside ransomware started showing up in infections targeting manufacturers and law firms in Europe and the U.S.

It’s not known how many victims have paid ransoms or how much the Darkside developers and their affiliates have earned from their criminal enterprise, but by any measure they’ve been very successful. Intel 471 reports that one victim hit in January 2021 was ordered to pay a $30 million ransom. Although they managed to negotiate it down to about a third of this, the payment would have made the recipients very rich. They’ve achieved such stellar success in part by being picky about their victims. Darkside’s administrators say that, out of principle, they won’t let their affiliates infect hospitals, schools and universities, non-profit organizations or government entities. But these restrictions have probably less to do with ethical considerations than monetary; these aren’t the kind of victims who can pay big ransoms.

“Before we attack we carefully analyze your accountancy and determine how much you can pay based on your net income,” the Darkside team notes in one of their posts.

Mark Arena, CEO of Intel 471 says the group is also picky about who can purchase its services, which means they have more control over how it’s used. The developers advertise only on Russian-language cybercriminal forums and "specifically say they don't want to work with English speakers,” Arena says. This means that most or all of the criminals purchasing Darkside’s services to extort victims are Russian-speaking. Arena provided the text from one Darkside advertisement, which was written in Russian:

Who are we NOT looking for

- English-speaking individuals.

- Dodgy individuals, employees of intelligence agencies, and analysts of information security companies.

- Those who set up RDP hosts and do things other than supplying networks.

- Any projects or offers that are not related to this post.

- Those who want to learn pentesting and earn millions.

- Those who demand a 100-M ransom for 3.5 servers.

It’s not clear how many victims the Darkside actors infected before they hit the U.S. holding company in August 2020. By the time they publicly debuted their new tool on August 10, they had already been infecting victims for months or longer with the tool. They, or one of their affiliates, had hacked the holding company three to six months before the August 10 announcement. And a recent report from the security firm Mandiant suggests the group had been active even longer than this. Mandiant describes a group it calls UNC2465 that was infecting victims with Darkside ransomware as early as April 2019.

Regardless of this, it appears their quality-assurance team was still working out kinks in their new product because Boyce says the decryption tool the hackers provided the holding company after it paid the ransom was buggy and had to be tweaked to get it to unlock all of the victim’s systems.

“The initial victims were essentially [Darkside’s] beta testers,” says Boyce.

Anatomy of a Recovery

It was the evening of Friday August 7 when the holding company’s 5,000 systems froze, alerting them to the presence of intruders in their network. The next morning, the company contacted Crypsis to investigate. Boyce, who headed Crypsis’ incident-response team at the time, spent most of that day at a wedding, glued to his phone.

“There’s a picture of me at the wedding in my suit, cocktail hour, on the phone talking to the victim,” he recalls.

It was immediately clear that they were dealing with a new ransomware strain that hadn’t been written about before.

“[T]here was nothing out there on Darkside at all,” he said, indicating an absence of prior reports about the ransomware from other digital forensic investigators.

Their first task was to map the holding company’s network to understand its architecture — how many systems were connected and how they were connected to each other. Saturday night they began pulling system logs to investigate. Ransomware only encrypts user files, not system files, so logs tracking activity on the network — what occurred, when it occurred, and who did it — are preserved, as long as the attackers haven’t deleted them to hide their tracks.

In this case, the holding company’s logs provided a good chart for Boyce and his team to trace the breach back to a phishing email. The email contained a link to a malicious web site that, when an employee visited the site, downloaded malware to their computer. The hackers then moved from that machine through the network to install a backdoor that gave them in-and-out access. In the context of everyday ransomware intrusions, it was nothing special.

“We didn't see anything sophisticated at all. It was normal ransomware by the playbook,” Boyce says. “Easy entry from a user computer, [aided by] poor IT practices.”

The latter included network administrators who shared and re-used administrative passwords. Once the intruders grabbed these credentials, they were able to access servers they needed to deploy the ransomware across systems company-wide. But they didn’t deploy their tool immediately. Instead they went silent for months.

“There was no active reconnaissance in the months between initial point-of-access and ransomware deployment,” Boyce says. “They got access, maintained their backdoor and persistence [on the network], and then once they were ready to launch their ransomware, it was launched.”

While Boyce's team investigated the breach, the payment negotiations were handled by Coveware.

“Payment [occurred] about five to seven days after a lot of back-and-forth [with the criminals],” Boyce says.

A separate recovery team hired by the holding company worked with the company’s own staff to set up a new network and decrypt the locked systems.

But once they got the decryption tool from the Darkside hackers, the recovery team found it didn’t work to unlock all of the systems owned by the company’s infected subsidiaries. This isn’t unusual says Boyce; sometimes ransomware developers will only make a decryption tool that works for computers using Windows 10 but not Windows XP. The recovery team had to troubleshoot with the criminal gang to get it to work.

The recovery team made sure the decryption tool didn’t contain malicious code, then began unlocking and restoring the holding company’s data — focusing on business-critical files first. It took four to six weeks to get every system, including those belonging to subsidiaries, decrypted, Boyce says.

In any ransomware infection, recovery teams advise victims to start from scratch with a new network — hardware and software — which can be created almost instantaneously, Boyce says. Once that network is in place, teams can populate the new network with files restored from trustworthy backups, not from servers that had been encrypted.

Ransomware actors are unlikely to alter or corrupt data on systems before encrypting them — since victims would be less likely to pay if it were known they were doing this — but even if the hackers didn’t manipulate data, the process of decrypting files can sometimes corrupt them or undermine their integrity, Boyce says.

“With decrypting, you’re relying on the criminal enterprise to essentially write good code to decrypt [your files],” Boyce says. “Often the program they give you to decrypt doesn't necessarily work one-hundred percent of the time.”

Company backups rarely include personal and individual work files from an employee’s desktop computer — they generally include only files that are essential to the core business and operations. This means that restoration from backups doesn’t recover everything, which is why a victim would still want to get access to machines that were locked by the ransomware.

After a ransomware infection, Boyce says recovery teams never re-connect infected systems to the new network or put those infected systems online. Instead they decrypt and recover files from them based on priority, scanning them for malware before loading them onto systems on the new network. It can take years, Boyce says, to fully recover from a ransomware infection, and companies infected with ransomware have to hold on to the data from their decrypted systems because they never know when they might need a file.

“You almost need to operate two infrastructures probably for years, and [gradually] segment out the impacted systems,” Boyce says.

Asked if the holding company felt they’d made a good decision in paying the ransom, Boyce says they did.

“In terms of the outcome, given that they weren’t named on the [Darkside] web site, they were pleased,” he says.

If you found this story valuable, please consider sharing it.

If you’d like to receive other stories like this, please consider subscribing.